A few years ago I came across an amusing Slashdot story: ‘Australian Gov’t offers $560k Cryptographic Protocol for Free‘. The story concerned a protocol developed by Australia’s Centrelink, the equivalent of our Health and Human Services department, that was wonderfully named the Protocol for Lightweight Authentication of ID, or (I kid you not), ‘PLAID‘.

A few years ago I came across an amusing Slashdot story: ‘Australian Gov’t offers $560k Cryptographic Protocol for Free‘. The story concerned a protocol developed by Australia’s Centrelink, the equivalent of our Health and Human Services department, that was wonderfully named the Protocol for Lightweight Authentication of ID, or (I kid you not), ‘PLAID‘.

Now to me this headline did not inspire a lot of confidence. I’m a great believer in TANSTAAFL — in cryptographic protocol design and in life. I figure if someone has to use ‘free’ to lure you in the door, there’s a good chance they’re waiting in the other side with a hammer and a bottle of chloroform, or whatever the cryptographic equivalent might be.

A quick look at PLAID didn’t disappoint. The designers used ECB like it was going out of style; did unadvisable things with RSA encryption, and that was only the beginning.

What PLAID was not, I thought at the time, was bad to the point of being exploitable. Moreover, I got the idea that nobody would use the thing. It appears I was badly wrong on both counts.

This is apropos of a new paper authored by Degabriele, Fehr, Fischlin, Gagliardoni, Günther, Marson, Mittelbach and Paterson entitled ‘Unpicking Plaid: A Cryptographic Analysis of an ISO-standards-track Authentication Protocol‘. Not to be cute about it, but this paper shows that PLAID is, well, bad.

As is typical for this kind of post, I’m going to tackle the rest of the content in a ‘fun’ question and answer format.

What is PLAID?

In researching this blog post I was somewhat amazed to find that Australians not only have universal healthcare, but that they even occasionally require healthcare. That this surprised me is likely due to the fact that my knowledge of Australia mainly comes from the first two Crocodile Dundee movies.

It seems that not only do Australians have healthcare, but they also have access to a ‘smart’ ID card that allows them to authenticate themselves. These contactless smartcards run the proprietary PLAID protocol, which handles all of the ugly steps in authenticating the bearer, while also providing some very complicated protections to prevent user tracking.

This protocol has been standardized as Australian standard AS-5185-2010 and is currently “in the fast track standardization process for ISO/IEC 25185-1.2”. You can obtain your own copy of the standard for a mere 118 Swiss Francs, which my currency converter tells me is entirely too much money. So I’ll do my best to provide the essential details in this post — and many others are in the research paper.

How does PLAID work?

|

| Accompanying tinfoil hat not pictured. |

PLAID is primarily an identification and authentication protocol, but it also attempts to offer its users a strong form of privacy. Specifically, it attempts to ensure that only authorized readers can scan your card and determine who you are.

This is a laudable goal, since contactless smartcards are ‘promiscuous’, meaning that they can be scanned by anyone with the right equipment. Countless research papers have been written on tracking RFID devices, so the PLAID designers had to think hard about how they were going to prevent this sort of issue.

Before we get to what steps the PLAID designers took, let’s talk about what one shouldn’t do in building such systems.

Let’s imagine you have a smartcard talking to a reader where anyone can query the card. The primary goal of an authentication protocol is to perform some sort of mutual authentication handshake and derive a session key that the card can use to exchange sensitive data. The naive protocol might look like this:

|

| Naive approach to an authentication protocol. The card identifies itself before the key agreement protocol is run, so the reader can look up a card-specific key. |

The obvious problem with this protocol is that it reveals the card ID number to anyone who asks. Yet such identification appears necessary, since each card will have its own secret key material — and the reader must know the card’s key in order to run an authenticated key agreement protocol.

PLAID solves this problem by storing a set of RSA public keys corresponding to various authorized applications. When the reader says “Hi, I’m a hospital“, a PLAID card determines which public key it use to talk to hospitals, then encrypts data under the key and sends it over. Only a legitimate hospital should know the corresponding RSA secret key to decrypt this value.

So what’s the problem here?

PLAID’s approach would be peachy if there were only one public key to deal with. However PLAID cards can be provisioned to support many applications (called ‘capabilities’). For example, a citizen who routinely finds himself wrestling crocodiles might possess a capability unique to the Reptile Wound Treatment unit of a local hospital.* If the card responds to this capability, it potentially leaks information about the bearer.

To solve this problem, PLAID cards do some truly funny stuff.

Specifically, when a reader queries the card, the reader initially transmits a set of capabilities that it will support (e.g., ‘hospital’, ‘bank’, ‘social security center’). If the PLAID card has been provisioned with a matching public key, it goes ahead and uses it. If no matching key is found, however, the card does not send an error — since this would reveal user-specific information. Instead, it fakes a response by encrypting junk under a special ‘dummy’ RSA public key (called a ‘shill key’) that’s stored within the card. And herein lies the problem.

You see, the ‘shill key’ is unique to each card, which presents a completely new avenue for tracking individual cards. If an attacker can induce an error and subsequently fingerprint the resulting RSA ciphertext — that is, figure out which shill key was used to encipher it — they can potentially identify your card the next time they encounter you.

|

| A portion of the PLAID protocol (source). The reader (IFD) is on the left, the card (ICC) is on the right. |

Thus the problem of tracking PLAID cards devolves to one of matching RSA ciphertexts to unknown public keys. The PLAID designers assumed this would not be possible. What Degabriele et al. show is that they were wrong.

What do German Tanks have to do with RSA encryption?

To distinguish the RSA moduli of two different cards, the researchers employed of an old solution to a problem called the German Tank Problem. As the name implies, this is a real statistical problem that the allies ran up against during WWII.

The problem can be described as follows:

Imagine that a factory is producing tanks, where each tank is printed with a sequential serial number in the ordered sequence 1, 2, …, N. Through battlefield captures you then obtain a small and (presumably) random subset of k tanks. From the recovered serial numbers, your job is to estimate N, the total number of tanks produced by the factory.

Happily, this is the rare statistical problem with a beautifully simple solution.** Let m be the maximum serial number in the set of k tanks you’ve observed. To obtain a rough guess Ñ for the total number of tanks produced, you can simply compute the following formula:

So what’s this got to do with guessing an unknown RSA key?

Well, this turns out to be another instance of exactly the same problem. Imagine that I can repeatedly query your card with bogus ‘capabilities’ and thus cause it to enter its error state. To foil tracking, the card will send me a random RSA ciphertext encrypted with its (card-specific) “shill key”. I don’t know the public modulus N corresponding to your key, but I do know that the ciphertext was computed using the standard RSA encryption formula m^e mod N.

My goal, as it was with the tanks, is to make a guess for N.

It’s worth pointing out that RSA is a permutation, which means that, provided the plaintext messages are randomly distributed, the ciphertexts will be randomly distributed as well. So all I need to do is collect a number of ciphertexts and apply the equation above. The resulting guess Ñ should then serve as a (fuzzy) identifier for any given card.

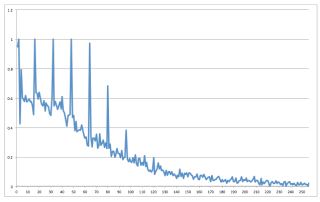

Now obviously this isn’t the whole story — the value Ñ isn’t exact, and you’ll get different levels of error depending on how many ciphertexts you get, and how many cards you have to distinguish amongst. But as the chart above shows, it’s possible to identify a specific card within in a real system (containing 100 cards) with reasonable probability.

But that’s not realistic at all. What if there are other cards in play?

It’s important to note that real life is nothing like a laboratory experiment. The experiment above considered a ‘universe’ consisting of only 100 cards, required an initial ‘training period’ of 1000 scans for a given card, and subsequent recognition demanded anywhere from 50 to 1000 scans of the card.

Since the authentication time for the cards is about 300 milliseconds per scan, this means that even the minimal number (50) of scans still requires about 15 seconds, and only produces the correct result with about 12% probability. This probability goes up dramatically the more scans you get to make.

Nonetheless, even the 50-scan result is significantly better than guessing, and with more concerted scans can be greatly improved. What this attack primarily serves to prove is that homebrew solutions are your enemy. Cooking up a clever approach to foiling tracking might seem like the right way to tackle a problem, but sometimes it can make you even more vulnerable than you were before.

How should one do this right?

The basic property that the PLAID designers were trying to achieve with this protocol is something called key privacy. Roughly speaking, a key private cryptosystem ensures that an attacker cannot link a given ciphertext (or collection of ciphertexts) to the public key that created them — even if the attacker knows the public key itself.

There are many excellent cryptosystems that provide strong key privacy. Ironically, most are more efficient than RSA; one solution to the PLAID problem is simply to switch to one of these. For example, many elliptic-curve (Diffie-Hellman or Elgamal) solutions will generally provide strong key privacy, provided that all public keys in the system are set in the same group.

A smartcard encryption scheme based on, say, Curve25519 would likely avoid most of the problems presented above, and might also be significantly faster to boot.

What else should I know about PLAID?

In addition to the shill key fingerprinting attacks, the authors also show how to identify the set of capabilities that a card supports, using a relatively efficient binary search approach. Beyond this, there are also many significantly more mundane flaws due to improper use of cryptography.

By far the ugliest of these are the protocol’s lack of proper RSA-OAEP padding, which may present potential (but implementation specific) vulnerabilities to Bleichenbacher’s attack. There’s also some almost de rigueur misuse of CBC mode encryption, and a handful of other flaws that should serve as audit flags if you ever run into them in the wild.

At the end of the day, bugs in protocols like PLAID mainly help to illustrate the difficulty of designing secure protocols from scratch. They also keep cryptographers busy with publications, so perhaps I shouldn’t complain too much.

You should probably read up a bit on Australia before you post again.

I would note that this really isn’t a question. But it’s absolutely true. And to this end: I would sincerely like to apologize to any Australian citizens who may have been offended by this post.

Notes:

* This capability is not explicitly described in the PLAID specification.

** The solution presented here — and used in the paper — is the frequentist approach to the problem. There is also a Bayesian approach, but it isn’t required for this application.