Apologies in advance for a super-wonky post, but I’m in kind of a wonky mood this week. It happens that I’m putting together a talk on the subject of circular security, and I figured this blog might be a good place to get my thoughts together.

If you’ve never heard of circular security, don’t feel bad — you’re in good company. In a nutshell, circular security describes the way that an encryption scheme behaves when you ask it to encrypt its own key. In theory, that behavior can be pretty unpredictable.

The key word in the previous sentence is ‘theory’. Circular security is a very interesting research area, but if your primary reason for reading this blog is to learn about practical things, this post may not be for you. (Though please come back next week, when I hope to be writing about electronic cash!)

Assuming you’re still reading, the first order of business is to talk about what circular security (or insecurity) is in the first place. To do that, we need to define what it means for an encryption scheme to be ‘secure’. And that means a discussion of semantic security.

Semantic Security

Semantic security is one of the earliest and most important security definitions in our field. It’s generally considered to be the minimum bar for any modern ‘secure’ encryption scheme. In English, the informal definition of semantic security is something like this:

An attacker who sees the encryption of a message — drawn from a known, or even chosen message space — gains approximately the same amount of information as they would have obtained if they didn’t see the encryption in the first place. (The one exception being the length of the message.)

This is a nice, intuitive definition since it captures what we really want from encryption.

You see, in an ideal world, we wouldn’t need encryption at all. We would send all of our data via some sort of magical, buried cable that our adversary couldn’t tap. Unfortunately, in the real world we don’t have magical cables: we send our data via the public WiFi at our neighborhood Starbucks.

Semantic security tells us not to worry. As long as we encrypt with a semantically-secure scheme, the adversary who intercepts our encrypted data won’t learn much more than the guy who didn’t intercept it at all — at worst, he’ll learn only the amount of data we sent. Voila, security achieved.

(Now, just for completeness: semantic security is not the strongest definition we use for security, since it does not envision active attacks, where the adversary can obtain the decryption of chosen ciphertexts. But that’s a point for another time.)

Unfortunately, before we can do anything with semantic security, we need to turn the English-language intuition above into something formal and mathematical. This is surprisingly complicated, since it requires us to formalize the notion of ‘an attacker gains approximately the same amount of information‘. In the early definitions this was done by making grand statements about predicate functions. This approach is faithful and accurate. It’s also kind of hard to do anything with.

Fortunately there’s a much simpler, yet equivalent way to define semantic security. This definition is called ‘indistinguishability under chosen plaintext attack‘, or IND-CPA for short. IND-CPA is described by the following game which is ‘played’ between an adversary and some honest party that we’ll call the challenger:

- The challenger generates a public/private keypair, and gives the public key to the adversary.

- The adversary eventually picks two equal-length messages (M0, M1) from the set of allowed plaintexts, and sends them to the challenger.

- The challenger flips a coin, then returns the encryption of one of the messages under the public key.

- The attacker tries to guess which message was encrypted. He ‘wins’ if he guesses correctly.

(This game can also be applied to symmetric encryption. Since there’s no public key in a symmetric scheme, the challenger makes up the lost functionality by providing an encryption oracle: i.e., it encrypts messages for the adversary as she asks for them.)

And that leads us to our (basically) formal definition:

A scheme is IND-CPA secure if no adversary can win the above game with probability (significantly) greater than 1/2.

The term ‘significantly’ in this case hides a lot of detail — typically it means that ‘non-negligibly‘. In many schemes we also require the adversary to run in limited time (i.e., be a probabilistic polynomial-time Turing machine). But details, details…

Encrypting your own key

One of the weirder aspects of the IND-CPA definition above is that it doesn’t handle a very basic (and surprisingly common!) use case: namely, cases where you encrypt your own secret key.

Believe it or not, this actually happens. If you use a disk encryption system like Bitlocker, you maybe already be encrypting your own keys, without even noticing it. Moreover, newer schemes like Gentry’s Fully Homomorphic Encryption depend fundamentally on this kind of “circular” encryption.

It seems surprising that IND-CPA can give us such a strong notion of security — where the attacker learns nothing about a plaintext — and yet can’t handle this very simple case. After all, isn’t your secret key just another message? What makes it special?

The technical answer to this question hangs on the fact that the IND-CPA game above only works with messages chosen by the adversary. Specifically, the adversary is asked to attack the encryption of either M0 or M1, which he chooses in step (2). Since presumably — if the scheme is secure — the adversary doesn’t know the scheme’s secret key, he won’t be able to submit (M0,M1) such that either message contains the scheme’s secret key. (Unless he makes a lucky guess, but this should happen with at most negligible probability.)

What this means is that an encryption scheme could do something terribly insecure when asked to encrypt its own secret key. For example, it could burp out the secret key without encrypting it at all! And yet it would still satisfy the IND-CPA definition. Yikes! And once you raise the possibility that such a scheme could exist, cryptographers will immediately wants to actually build it.

(This may seem a little perverse: after all, aren’t there enough broken schemes in the world without deliberately building more? But when you think about it, this kind of ‘counterexample’ is extremely valuable to us. If we know that such oddball, insecure schemes can exist, that motivates to watch out for them in the real constructions that we use. And it tells us a little about the strength of our definitions.)

It turns out that there’s a ‘folklore’ approach that turns any IND-CPA secure public-key encryption scheme into one that’s still IND-CPA secure, but is also totally insecure if it ever should encrypt its own secret key.

The basic approach is to modify the original scheme by changing the encryption algorithm as follows:

- On input a public key and a message to be encrypted, it tests to see if the message is equal to the scheme’s secret key.*

- If not, it encrypts the message using the original scheme’s encryption algorithm (which, as we noted previously, is IND-CPA secure).

- If the message is equal to the secret key, it just outputs the secret key in cleartext.

Circles and cycles

Just as cryptographers were congratulating each other for answering the previous question — showing that there are schemes that fail catastrophically when they encrypt their own secret key — some smartass decided to up the stakes.

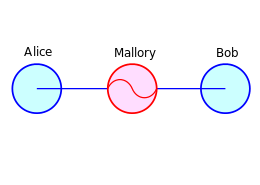

Let’s be clear what I’m saying here. Imagine that Alice decides to entrust Bob with her secret key, so she wraps it up under his public key (say, sending him a PGP encrypted email). And imagine that Bob decides to do exactly the same with his key, encrypting it under Alice’s public key. We now have the following ‘key cycle’:

CA = Encrypt(pkA, skB), CB = Encrypt(pkB, skA)

To be clear, IND-CPA by itself tells us that it’s perfectly secure for Alice to encrypt her own key under Bob’s key (or vice versa). There’s no problem there. However, the minute Bob also encrypts Alice’s secret key, a cycle is formed — and semantic security doesn’t tell us anything about whether this is secure.

So this is worrisome in theory, but are there actual schemes where such cycles can cause problem?

Up until 2010, the answer was: no. It turns out to be much harder to find a counterexample for this case, since the approach described in the previous section doesn’t work. You can’t just hack a little bit of code into the encryption algorithm; the ciphertexts are encrypted independently. At the time they’re encrypted, the ciphertexts are perfectly secure. They only become insecure when they come into close proximity with one another.

(If a weird analogy helps, think of those encrypted keys like two hunks of Plutonium, each inside of its own briefcase. As long as they’re apart, everything’s fine. But get them close enough to one another, they interact with one another and basically ruin your whole day.)

It gets worse

A breakthrough occurred at Eurocrypt 2010, where Acar, Belenkiy, Bellare and Cash showed that indeed, there is a scheme that’s perfectly IND-CPA secure in normal usage, but fails when Alice and Bob encrypt their keys in a cycle like the one described above.

The Acar et al. scheme is based on certain type of elliptic-curve setting known as bilinear SXDH, and what they show is that when Alice and Bob create a key cycle like the one above, an adversary can recognize it as such.

To be clear, what this means is that the ciphertexts (Encrypt(pkA, skB), Encrypt(pkB, skA)) jointly leak a little bit of information — simply the fact that they encrypt each other’s secret keys! This may not seem like much, but it’s far more than they should ever reveal.

The Acar et al. result is interesting to me, because along with my colleague Susan Hohenberger, I was thinking about the same problem around the same time. We independently came up with a similar finding just a few months after Acar et al. submitted theirs — crappy luck, but it happens. On the bright side, we discovered something slightly worse.

Specifically, we were able to construct a scheme that’s totally secure in normal usage, but becomes catastrophically insecure the minute Alice and Bob encrypt each others’ secret keys. This means in practice that if two parties innocently encrypt a key cycle, then both of their secret keys become public. This means every message that either party has ever encrypted (or will encrypt) becomes readable. Not good!**

The worst part is that both the Acar et al. scheme and our scheme are (almost) normal-looking constructions. They could be real schemes that someone came up with and deployed in the real world! And if they did, and if someone encrypted their secret keys in a cycle, things would be very bad for everyone.

So what do we do about this?

Unfortunately, building provably KDM-secure schemes is not an easy task, at least, not without resorting to artificial constructs like random oracles. While this may change in the future, for the moment we have a ways to go before we can build truly efficient schemes that don’t (potentially) have problems like the above.

And this is what makes cryptography so interesting. No matter what we say about our schemes being ‘provably secure’, the truth is: there’s always something we haven’t thought of. Just when you thought you’d finally solved all the major security problems (ha!), another one will always pop up to surprise you.

Notes:

* The obvious objection is that a public key encryption algorithm takes in only a public key and a message. It doesn’t take in the scheme’s secret key. So: how can it check whether the given message is the encryption of the secret key? There’s a general solution to this, but I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader.

** David Cash, Susan Hohenberger and I have summarized these results, along with several related to symmetric encryption, and will be presenting them at PKC 2012. If you’re interested, a full version of our paper should appear here shortly.

hacking group LulzSec. We now know that these arrests were facilitated by ‘Anonymous’ leader* “

hacking group LulzSec. We now know that these arrests were facilitated by ‘Anonymous’ leader* “