Last week we learned (from two different sources!) that certain RSA implementations don’t properly seed their random number generators before generating keys. One practical upshot is that a non-trivial fraction of RSA moduli share a prime factor. Given two such moduli, you can easily factor both.

Last week we learned (from two different sources!) that certain RSA implementations don’t properly seed their random number generators before generating keys. One practical upshot is that a non-trivial fraction of RSA moduli share a prime factor. Given two such moduli, you can easily factor both.

This key generation kerfuffle is just the tip of the iceberg: a lot of bad things can happen when you use a weak, or improperly-seeded RNG. To name a few:

- Re-using randomness with (EC)DSA can lead to key recovery.

- Re-using randomness with Elgamal can lead to plaintext recovery and other ugliness.

- Using predictable IVs in CBC or CTR mode encryption can lead to plaintext recovery.

- When protocols use predictable nonces they may become vulnerable to e.g., replay attacks.

In the rest of this post I’m going to talk about the various ways that random number generators work, the difference between RNGs and PRGs, and some of the funny problems with both. Since the post has gotten horrifically long, I’ve decided to present it in a (fun!) question/answer style that makes it easy to read in any order you want. Please feel free to skip around.

What’s the difference between Randomness, Pseudo-Randomness and Entropy?

Before we get started, we have to define a few of our terms. The fact is, there are many, many definitions of randomness. Since for our purposes we’re basically interested in random bit generators, I’m going to give a workaday definition: with a truly random bit generator, nobody (regardless of what information or computing power they have) can predict the next output bit with probability greater than 1/2.

|

| A hardware RNG. |

The most expensive hardware RNGs take advantage of this, measuring such phenomena as radioactive decay or shot noise. Most consumer-grade RNGs don’t have radioactive particles lying around, so they instead measure macroscopic, but chaotic phenomena — typically highly-amplified electrical noise.

These devices are great if you’ve got ’em; unfortunately not everyone does. For the rest of us, the solution is to collect unpredictable values from the computer we’re working on. While this gunk may not be truly random, we hope that it has sufficient entropy — essentially a measure of unpredictability — that our attacker won’t know the difference.

If you’re using a standard PC, your system is probably filling its entropy pool right now: from unpredictable values such as drive seek or inter-keystroke timings. Taken individually none of these events provide enough entropy to do much; but by ‘stirring’ many such measurements together you can obtain enough to do useful cryptography.

Random vs. Pseudorandom. The big problem with RNGs is that they’re usually pretty inefficient. Hardware RNGs can only collect so many bits per second, and the standard OS entropy measurement techniques are even slower. For this reason, many security systems don’t actually use this entropy directly. Instead, they use it to seed a fast cryptographically-secure pseudo-random generator, sometimes called a CSPRNG or (to cryptographers) just a PRG.

PRGs don’t generate random numbers at all. Rather, they’re algorithms that take in a short random string (‘seed’), and stretch it into a long sequence of random-looking bits. Since PRGs are deterministic and computational in nature, they obviously don’t satisfy our definition of randomness (a sufficiently powerful attacker can simply brute-force her way through the seed-space.) But if our attackers are normal (i.e., computationally limited) it’s possible to build unpredictable PRGs from fairly standard assumptions.*

You can argue about whether this is a good idea, but the upshot is as follows: if you want to understand where ‘random’ numbers come from, you really need to understand both technologies and how they interoperate on your machine.

Where does my entropy come from?

Unless you’re running a server and have a fancy Hardware Security Module installed, chances are that your system is collecting entropy from the world around it. Most OSes do this at the kernel level, using a variety of entropy sources which are then ‘stirred’ together. These include:

- Drive seek timings. Modern hard drives (of the spinning variety) are a wonderful source of chaotic events. In 1994 Davis, Ihaka and Fenstermacher argued that drive seek times are affected by air turbulence within the drive’s enclosure, which makes them an excellent candidate for cryptographic entropy sampling. It’s not clear how this technique holds up against solid-state drives; probably not well.

- Mouse and keyboard interaction. People are unpredictable. Fortunately for us, that’s a good thing. Many RNGs collect entropy by measuring the time between a user’s keystrokes or mouse movements, then gathering a couple of low-order bits and adding them to the pool.

- Network events. Although network events (packet timings, for example) seem pretty unpredictable, most systems won’t use this data unless you explicitly tell them to. That’s because the network is generally assumed to be under the adversary’s control (he may be the one sending you those ‘unpredictable’ packets!) You disable these protections at your own risk.

- Uninitialized memory. Ever forget to initialize a variable? Then you know that RAM is full of junk. While this stuff may not be random, certain systems use it on the theory that it probably can’t hurt. Occasionally it can — though not necessarily in the way you’d think. The classic example is this Debian OpenSSL bug, which (via a comedy of errors) meant that the PRG had only 32,768 possible seed values.

- Goofy stuff. Some systems will try to collect entropy by conducting unpredictable calculations. One example is to start many threads counting towards infinity, then stop one with a hardware interrupt. I’ve done this once before and evaluated the output. I assure you that YMMV. Significantly.

- Trusted Platform Module. Many desktop machines these days include a TPM chip on the motherboard. The good news about this is that every TPM contains an internal hardware RNG, which your OS can access if it has the right drivers. It ain’t fast, and the design hasn’t been publicly audited. Still, folding some of this into your entropy pool is probably a good idea.

- New processor RNGs. To save us all this trouble, the next generation of Intel processors will contain a built-in hardware RNG/PRG, which goes by the codename ‘Bull Mountain’. Perhaps this will be the solution to all of our problems. (h/t David Johnston in comments.)

The upshot of all of this is that on a typical machine there’s usually enough ‘unpredictable’ stuff going on to seed a decent entropy pool. The real problems come up in systems that aren’t typical.

What about VMs and embedded devices?

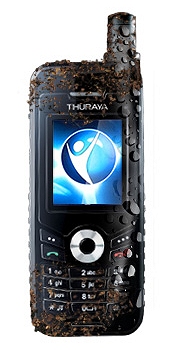

|

| Life inside an embedded device. |

The problem with classical entropy gathering is that it assumes that unpredictable things will actually happen on the system. Unfortunately, VMs and embedded devices defy this expectation, mostly by being very, very boring.

Imagine the following scenario: you have a VM instance running on a server. It has no access to keyboard or mouse input, and only mediated access to hardware, which it shares with eight other VM instances.

Worse yet, your VM may be a clone. Perhaps you just burped up fifty instances of that particular image from a ‘frozen’ state. Each of these VMs may have loads of entropy in its pool, but it’s all the same entropy, across every clone sibling. Whether this is a problem depends on what the VM does next. If it has enough time to replenish its entropy pool, the state of the VMs will gradually diverge. But if it decides to generate a key: not good at all.

Embedded devices present their own class of problems. Unfortunately (like every other problem in the embedded arena) there’s no general solution. Some people obtain entropy from user keypad timings — if there is a user and a keypad. Some use the low-order bits of the ADC output. Still others forgo this entirely and ship their devices with an externally-generated PRG seed, usually stored in NVRAM.

I don’t claim that any of these are good answers, but they’re better than the alternative — which is to pretend that you have entropy when you don’t.

How do pseudo-random number generators work?

You’ve read the books. You’ve seen the movies. But when it comes down to it you still don’t understand the inner workings of the typical pseudo-random number generator. I can’t possibly make up for this in a single blog post, but hopefully I can hit a few of the high points.

Block cipher-based PRGs. One common approach to PRG construction uses a block cipher to generate unpredictable bits. This seems like a reasonable choice, since modern block ciphers are judged for their quality as pseudo-random permutations, and because most crypto libraries already have one lying around somewhere.

|

| ANSI X9.31 PRNG implemented with AES (source). At each iteration, the PRNG takes in a predictable ‘date-time vector’ (DTi) and updated state value (Si). It outputs a block of random bits Ri. The generator is seeded with a cipher key (k) and an initial state S0. |

One inexplicably popular design comes from ANSI X9.31. This PRG is blessed by both ANSI and FIPS, and gets used in a lot of commercial products (OpenSSL also uses it in FIPS mode). It takes in two seeds, k and S0 and does pretty much what you’d expect, on two conditions: you seed both values, and you never, ever reveal k.

If k does leak out, things can get ugly. With knowledge of k your attacker can calculate every previous and future PRG output from one single block of output!** This is totally gratuitous, and makes you wonder why this particular design was ever chosen — much less promoted.

Before you dismiss this as a theoretical concern: people routinely make stupid mistakes with X9.31. For example, an early draft of the AACS standard proposed to share one k across many different devices! Moreover keys do get stolen, and when this happens to your RNG you risk compromising every previous transaction on the system — even supposedly ‘forward-secure’ ones like ephemeral ECDH key exchanges. You can mitigate this by reseeding k periodically.

Hash-based PRGs. Many PRGs do something similar, but using hash functions instead of ciphers. There are some good arguments for this: hash functions are very fast, plus they’re hard to invert — which can help to prevent rewinding attacks on PRG state. Since there are zillions of hash-based PRGs I’ll restrict this discussion to a few of the most common ones:

- FIPS 186-2 (Appendix 3) defines a SHA-based generator that seems to be all the rage, despite the fact that it was nominally defined only for DSA signing. Windows uses this as its default PRG.

- Linux uses a hash-based PRG based on two variants of SHA.

- The non-FIPS OpenSSL PRG also uses a hash-based design. Like everything else in OpenSSL, it’s clearly documented and follows standard, well-articulated design principles.

|

| Left: the Linux PRG (circa 2006). Right: the non-FIPS OpenSSL PRG. |

Number-theoretic PRGs. The problem with basing a PRG on, say, a hash function is it makes you dependent on the security of that primitive. If a the hash turns out to be vulnerable, then your PRG could be as well.*** (Admittedly, if this happens to a standard hash function, the security of your PRG may be the least of your concerns.)

One alternative is to use a PRG that relies on well-studied mathematical assumptions for its security. Usually, you pay a heavy cost for this hypothetical benefit — these generators can be 2-3 orders of magnitude slower than their hash-based cousins. Still, if you’re down for this you have various choices. An oldie (but goodie) is Blum-Blum-Shub, which is provably secure under the factoring assumption.

If you like standards, NIST also has a proposal called Dual-EC-DRBG. Dual-EC is particularly fascinating, for the following three reasons. First, it’s built into Windows, which probably makes it the most widely deployed number-theoretic PRG in existence. Second, it’s slightly biased, due to a ‘mistake’ in the way that NIST converted EC points into bits.**** Also, it might contain a backdoor.

This last was pointed out by Shumow and Ferguson at the Crypto 2007 rump session. They noticed that the standard parameters given with Dual-EC could easily hide a trapdoor. Anyone who knew this value would be able to calculate all future outputs of the PRG after seeing only a 32-byte chunk of its output! Although there’s probably no conspiracy here, NSA’s complicity in designing the thing doesn’t make anyone feel better about it.

|

| Shrinking generator. |

The rest. There are many dedicated PRG constructions that don’t fit into the categories above. These include stream ciphers like RC4, not to mention a host of crazy LFSR-based things. All I can say is: if you’re going to use something nonstandard, please make sure you have a good reason.

How much entropy do I need?

The general recommendation is that you need to seed your PRG with at least as much entropy as the security level of your algorithms. If you’re generating 1024-bit RSA keys, the naive theory tells you that you need at least 80 bits of entropy, since this is the level of security provided by RSA at that key size.

In practice you need more, possibly as much as twice the security level, depending on your PRG. The problem is that many PRNGs have an upper bound on the seed size, which means they can’t practically achieve levels higher than, say, 256 bits. This is important to recognize, but it’s probably not of any immediate practical consequence.

I don’t care about any of this, just tell me how to get good random numbers on my Linux/Windows/BSD system!

The good news for you is that modern operating systems and (non-embedded) hardware provide most of what you need, meaning that you’re free to remain blissfully ignorant.

On most Unix systems you can get decent random numbers by reading from /dev/random and /dev/urandom devices. The former draws entropy from a variety of system sources and hashes it together, while the latter is essentially a PRG that seeds itself from the system’s entropy pool. Windows can provide you with essentially the same thing via the CryptoAPI (CAPI)’s CryptGenRandom call.

Care must be taken in each of these cases, particularly as your application is now dependent on something you don’t control. Many cryptographic libraries (e.g., OpenSSL) will run their own internal PRG, which they seed from sources like the above.

I’ve designed my own PRG. Is this a good idea?

Maybe. But to be completely honest, it probably isn’t.

If I seed my PRG properly, is it safe to use RSA again?

Yes. Despite the title of the recent Lenstra et al. paper, there’s nothing wrong with RSA. What seems to have happened is that some embedded systems didn’t properly seed their (P)RNGs before generating keys.

I’m sure there’s more to it than that, but at a high level: if you make sure to properly seed your PRG, the probability that you’ll repeat a prime is negligibly small. In other words, don’t sweat it.

Notes:

* The security definition for a PRG is simple: no (computationally limited) adversary should be able to distinguish the output of a PRG from a sequence of ‘true’ random numbers, except with a negligible probability. An equivalent definition is the ‘next bit test’, which holds that no adversary can predict the next bit output by a PRG with probability substantially different from 1/2.

** Decrypting Ri gives you (Si XOR Ii), and decrypting DTi gives you Ii. You can now calculate Si by XORing the results. If you know DT{i-1} you can now compute R{i-1} and start the process over again. This was first noted by Kelsey, Schneier, Wagner and Hall in the context of an early version (X9.17). It works even if you only have a rough guess for the timestamp values — a pretty reasonable assumption, since some implementations specify a counter for the DT values.

*** It’s also important to be clear what security properties you’re relying on with a hash-based PRG. Most of the high-profile attacks on hash functions (e.g., MD5) focus on finding collisions; they’re not attacks on the pseudo-random nature of the outputs. In practice, this means you usually get lots of warning before a hash function becomes unsuitable for use in a PRG. Or maybe you won’t! Fun stuff.

**** Dual-EC is another fun example of NIST developing provably-secure looking protocols, but not actually including a security proof. This is particularly bizarre, because the only conceivable reason to use something as slow as Dual-EC is to gain this level of provable security. The generator is divided into two parts: the first generates pseudo-random EC points (this part is provable under the DDH assumption). The other part turns these points into bits. It’s the latter part that has the biasing flaw. Amusingly, the potential ‘backdoor’ wouldn’t be possible if the designers had built this part differently.

subordinate root (‘skeleton’) certificates to their corporate clients, for the explicit purpose of

subordinate root (‘skeleton’) certificates to their corporate clients, for the explicit purpose of

bad guys figure out how to neutralize

bad guys figure out how to neutralize