Yesterday I happened upon a Wired piece by Steven Levy that covers Ray Ozzie’s proposal for “CLEAR”. I’m quoted at the end of the piece (saying nothing  much), so I knew the piece was coming. But since many of the things I said to Levy were fairly skeptical — and most didn’t make it into the piece — I figured it might be worthwhile to say a few of them here.

much), so I knew the piece was coming. But since many of the things I said to Levy were fairly skeptical — and most didn’t make it into the piece — I figured it might be worthwhile to say a few of them here.

Ozzie’s proposal is effectively a key escrow system for encrypted phones. It’s receiving attention now due to the fact that Ozzie has a stellar reputation in the industry, and due to the fact that it’s been lauded by law enforcement (and some famous people like Bill Gates). Ozzie’s idea is the just the latest bit of news in this second edition of the “Crypto Wars”, in which the FBI and various law enforcement agencies have been arguing for access to end-to-end encryption technologies — like phone storage and messaging — in the face of pretty strenuous opposition by (most of) the tech community.

In this post I’m going to sketch a few thoughts about Ozzie’s proposal, and about the debate in general. Since this is a cryptography blog, I’m mainly going to stick to the technical, and avoid the policy details (which are substantial). Also, since the full details of Ozzie’s proposal aren’t yet public — some are explained in the Levy piece and some in this patent — please forgive me if I get a few details wrong. I’ll gladly correct.

[Note: I’ve updated this post in several places in response to some feedback from Ray Ozzie. For the updated parts, look for the *. Also, Ozzie has posted some slides about his proposal.]

How to Encrypt a Phone

The Ozzie proposal doesn’t try tackle every form of encrypted data. Instead it focuses like a laser on the simple issue of encrypted phone storage. This is something that law enforcement has been extremely concerned about. It also represents the (relatively) low-hanging fruit of the crypto debate, for essentially two reasons: (1) there are only a few phone hardware manufacturers, and (2) access to an encrypted phone generally only takes place after law enforcement has gained physical access to it.

I’ve written about the details of encrypted phone storage in a couple of previous posts. A quick recap: most phone operating systems encrypt a large fraction of the data stored on your device. They do this using an encryption key that is (typically) derived from the user’s passcode. Many recent phones also strengthen this key by “tangling” it with secrets that are stored within the phone itself — typically with the assistance of a secure processor included in the phone. This further strengthens the device against simple password guessing attacks.

The upshot is that the FBI and local law enforcement have not — until very recently (more on that further below) — been able to obtain access to many of the phones they’ve obtained during investigation. This is due the fact that, by making the encryption key a function of the user’s passcode, manufacturers like Apple have effectively rendered themselves unable to assist law enforcement.

The Ozzie Escrow Proposal

Ozzie’s proposal is called “Clear”, and it’s fairly straightforward. Effectively, it calls for manufacturers (e.g., Apple) to deliberately put themselves back in the loop. To do this, Ozzie proposes a simple form of key escrow (or “passcode escrow”). I’m going to use Apple as our example in this discussion, but obviously the proposal will apply to other manufacturers as well.

Ozzie’s proposal works like this:

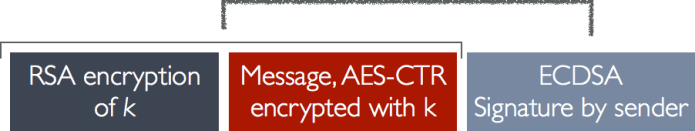

- Prior to manufacturing a phone, Apple will generate a public and secret “keypair” for some public key encryption scheme. They’ll install the public key into the phone, and keep the secret key in a “vault” where hopefully it will never be needed.

- When a user sets a new passcode onto their phone, the phone will encrypt a passcode under the Apple-provided public key. This won’t necessarily be the user’s passcode, but it will be an equivalent passcode that can unlock the phone.* It will store the encrypted result in the phone’s storage.

- In the unlikely event that the FBI (or police) obtain the phone and need to access its files, they’ll place the phone into some form of law enforcement recovery mode. Ozzie describes doing this with some special gesture, or “twist”. Alternatively, Ozzie says that Apple itself could do something more complicated, such as performing an interactive challenge/response with the phone in order to verify that it’s in the FBI’s possession.

- The phone will now hand the encrypted passcode to law enforcement. (In his patent, Ozzie suggests it might be displayed as a barcode on a screen.)

- The law enforcement agency will send this data to Apple, who will do a bunch of checks (to make sure this is a real phone and isn’t in the hands of criminals). Apple will access their secret key vault, and decrypt the passcode. They can then send this back to the FBI.

- Once the FBI enters this code, the phone will be “bricked”. Let me be more specific: Ozzie proposes that once activated, a secure chip inside the phone will now permanently “blow” several JTAG fuses monitored by the OS, placing the phone into a locked mode. By reading the value of those fuses as having been blown, the OS will never again overwrite its own storage, will never again talk to any network, and will become effectively unable to operate as a normal phone again.

When put into its essential form, this all seems pretty simple. That’s because it is. In fact, with the exception of the fancy “phone bricking” stuff in step (6), Ozzie’s proposal is a straightforward example of key escrow — a proposal that people have been making in various guises for many years. The devil is always in the details.

A vault of secrets

If we picture how the Ozzie proposal will change things for phone manufacturers, the most obvious new element is the key vault. This is not a metaphor. It literally refers to a giant, ultra-secure vault that will have to be maintained individually by different phone manufacturers. The security of this vault is no laughing matter, because it will ultimately store the master encryption key(s) for every single device that manufacturer ever makes. For Apple alone, that’s about a billion active devices.

Does this vault sound like it might become a target for organized criminals and well-funded foreign intelligence agencies? If it sounds that way to you, then you’ve hit on one of the most challenging problems with deploying key escrow systems at this scale. Centralized key repositories — that can decrypt every phone in the world — are basically a magnet for the sort of attackers you absolutely don’t want to be forced to defend yourself against.

So let’s be clear. Ozzie’s proposal relies fundamentally on the ability of manufacturers to secure extremely valuable key material for a massive number of devices against the strongest and most resourceful attackers on the planet. And not just rich companies like Apple. We’re also talking about the companies that make inexpensive phones and have a thinner profit margin. We’re also talking about many foreign-owned companies like ZTE and Samsung. This is key material that will be subject to near-constant access by the manufacturer’s employees, who will have to access these keys regularly in order to satisfy what may be thousands of law enforcement access requests every month.

If ever a single attacker gains access to that vault and is able to extract, a few “master” secret keys (Ozzie says that these master keys will be relatively small in size*) then the attackers will gain unencrypted access to every device in the world. Even better: if the attackers can do this surreptitiously, you’ll never know they did it.

Now in fairness, this element of Ozzie’s proposal isn’t really new. In fact, this key storage issue an inherent aspect of all massive-scale key escrow proposals. In the general case, the people who argue in favor of such proposals typically make two arguments:

- We already store lots of secret keys — for example, software signing keys — and things works out fine. So this isn’t really a new thing.

- Hardware Security Modules.

Let’s take these one at a time.

It is certainly true that software manufacturers do store secret keys, with varying degrees of success. For example, many software manufacturers (including Apple) store secret keys that they use to sign software updates. These keys are generally locked up in various ways, and are accessed periodically in order to sign new software. In theory they can be stored in hardened vaults, with biometric access controls (as the vaults Ozzie describes would have to be.)

But this is pretty much where the similarity ends. You don’t have to be a technical genius to recognize that there’s a world of difference between a key that gets accessed once every month — and can be revoked if it’s discovered in the wild — and a key that may be accessed dozens of times per day and will be effectively undetectable if it’s captured by a sophisticated adversary.

Moreover, signing keys leak all the time. The phenomenon is so common that journalists have given it a name: it’s called “Stuxnet-style code signing”. The name derives from the fact that the Stuxnet malware — the nation-state malware used to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program — was authenticated with valid code signing keys, many of which were (presumably) stolen from various software vendors. This practice hasn’t remained with nation states, unfortunately, and has now become common in retail malware.

The folks who argue in favor of key escrow proposals generally propose that these keys can be stored securely in special devices called Hardware Security Modules (HSMs). Many HSMs are quite solid. They are not magic, however, and they are certainly not up to the threat model that a massive-scale key escrow system would expose them to. Rather than being invulnerable, they continue to cough up vulnerabilities like this one. A single such vulnerability could be game-over for any key escrow system that used it.

In some follow up emails, Ozzie suggests that keys could be “rotated” periodically, ensuring that even after a key compromise the system could renew security eventually. He also emphasizes the security mechanisms (such as biometric access controls) that would be present in such a vault. I think that these are certainly valuable and necessary protections, but I’m not convinced that they would be sufficient.

Assume a secure processor

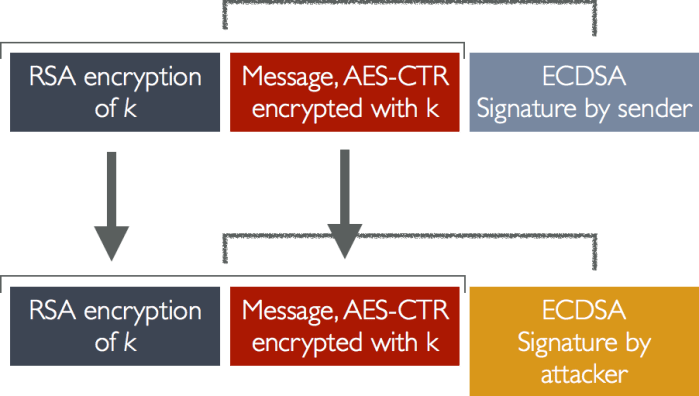

Let’s suppose for a second that an attacker does get access to the Apple (or Samsung, or ZTE) key vault. In the section above I addressed the likelihood of such an attack. Now let’s talk about the impact.

Ozzie’s proposal has one significant countermeasure against an attacker who wants to use these stolen keys to illegally spy on (access) your phone. Specifically, should an attacker attempt to illegally access your phone, the phone will be effectively destroyed. This doesn’t protect you from having your files read — that horse has fled the stable — but it should alert you to the fact that something fishy is going on. This is better than nothing.

This measure is pretty important, not only because it protects you against evil maid attacks. As far as I can tell, this protection is pretty much the only measure by which theft of the master decryption keys might ever be detected. So it had better work well.

The details on how this might work aren’t very clear in Ozzie’s patent, but the Wired article describes it as follows. This quote to repeat Ozzie’s presentation at Columbia University:

What Ozzie appears to describe here is a secure processor contained within every phone. This processor would be capable if securely and irreversibly enforcing that once law enforcement has accessed a phone, that phone could no longer be placed into an operational state.

My concern with this part of Ozzie’s proposal is fairly simple: this processor does not currently exist. To explain why this, let me tell a story.

Back in 2013, Apple began installing a secure processor in each of their phones. While this secure processor (called the Secure Enclave Processor, or SEP) is not exactly the same as the one Ozzie proposes, the overall security architecture seems very similar.

One main goal of Apple’s SEP was to limit the number of passcode guessing attempts that a user could make against a locked iPhone. In short, it was designed to keep track of each (failed) login attempt and keep a counter. If the number of attempts got too high, the SEP would make the user wait a while — in the best case — or actively destroy the phone’s keys. This last protection is effectively identical to Ozzie’s proposal. (With some modest differences: Ozzie proposes to “blow fuses” in the phone, rather than erasing a key; and he suggests that this event would triggered by entry of a recovery passcode.*)

For several years, the SEP appeared to do its job fairly effectively. Then in 2017, everything went wrong. Two firms, Cellebrite and Grayshift, announced that they had products that effectively unlocked every single Apple phone, without any need to dismantle the phone. Digging into the details of this exploit, it seems very clear that both firms — working independently — have found software exploits that somehow disable the protections that are supposed to be offered by the SEP.

The cost of this exploit (to police and other law enforcement)? About $3,000-$5,000 per phone. Or (if you like to buy rather than rent) about $15,000. Aso, just to add an element of comedy to the situation, the GrayKey source code appears to have recently been stolen. The attackers are extorting the company for two Bitcoin. Because 2018. (🤡👞)

Let me sum this up my point in case I’m not beating you about the head quite enough:

The richest and most sophisticated phone manufacturer in the entire world tried to build a processor that achieved goals similar to those Ozzie requires. And as of April 2018, after five years of trying, they have been unable to achieve this goal — a goal that is critical to the security of the Ozzie proposal as I understand it.

Now obviously the lack of a secure processor today doesn’t mean such a processor will never exist. However, let me propose a general rule: if your proposal fundamentally relies on a secure lock that nobody can ever break, then it’s on you to show me how to build that lock.

Conclusion

While this mainly concludes my notes about on Ozzie’s proposal, I want to conclude this post with a side note, a response to something I routinely hear from folks in the law enforcement community. This is the criticism that cryptographers are a bunch of naysayers who aren’t trying to solve “one of the most fundamental problems of our time”, and are instead just rejecting the problem with lazy claims that it “can’t work”.

As a researcher, my response to this is: phooey.

Cryptographers — myself most definitely included — love to solve crazy problems. We do this all the time. You want us to deploy a new cryptocurrency? No problem! Want us to build a system that conducts a sugar-beet auction using advanced multiparty computation techniques? Awesome. We’re there. No problem at all.

But there’s crazy and there’s crazy.

The reason so few of us are willing to bet on massive-scale key escrow systems is that we’ve thought about it and we don’t think it will work. We’ve looked at the threat model, the usage model, and the quality of hardware and software that exists today. Our informed opinion is that there’s no detection system for key theft, there’s no renewability system, HSMs are terrifically vulnerable (and the companies largely staffed with ex-intelligence employees), and insiders can be suborned. We’re not going to put the data of a few billion people on the line an environment where we believe with high probability that the system will fail.

Maybe that’s unreasonable. If so, I can live with that.

that researchers have spent the past forty years designing. We see this every day in examples ranging from

that researchers have spent the past forty years designing. We see this every day in examples ranging from