This post has been on my back burner for well over a year. This has bothered me, since with every month that goes by, I become more convinced that anonymous authentication the most important topic we could be talking about as cryptographers. This isn’t just because I love neat cryptography: it’s that I don’t trust the world we live in. I’m very worried that we’re headed into a privacy dystopia, driven largely by bad legislation and the proliferation of AI.

But this is a lot to kick off with. Let’s begin at the beginning.

One of the most important problems in computer security is user authentication. Every time you visit a website, log into a server, access a resource, you (and more realistically, your computer) must convince the provider that you’re authorized to access the resource. This authorization can take many forms. Some sites require explicit user logins, which users can realize with traditional username/passwords credentials, or (increasingly) advanced alternatives like MFA and passkeys. Other sites that don’t require explicit user credentials, or else they allow you to register a fully pseudonymous account; however even weakly-authenticating sites still ask user agents to prove something. Typically this is some kind of basic “anti-bot” check, which can be done with a combination of long-lived cookies, CAPTCHAs, or whatever the heck Cloudflare does:

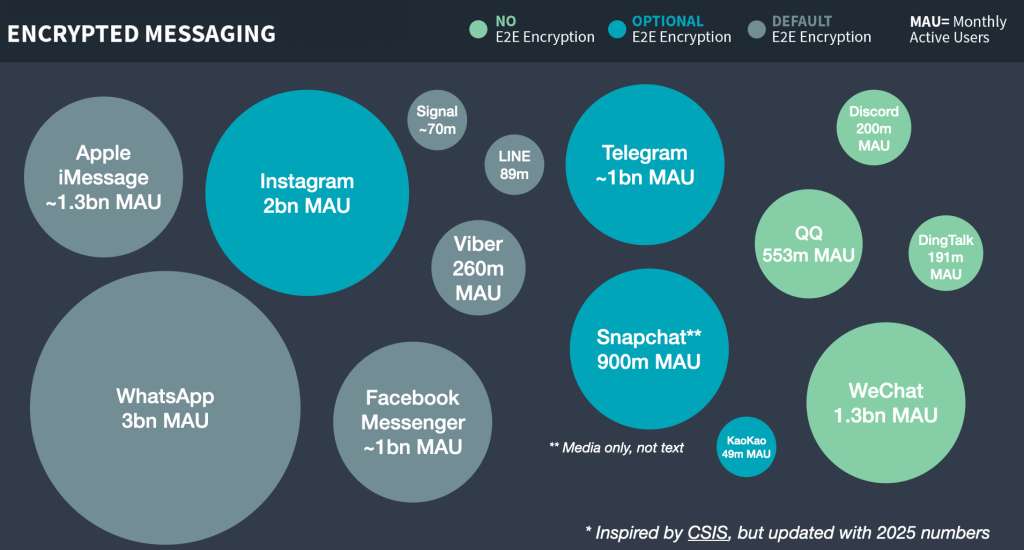

The Internet I grew up with was very casual about authentication: as long as you were willing to take basic steps to prevent abuse (make an account with a pseudonym, or just refrain from spamming), most sites seemed happy to allow somewhat-anonymous usage. Over the past few years this pattern has begun to change. In part this is because advertising-driven sites love to collect data, and knowing your exact identity makes you more lucrative as an advertising target. A more recent driver of the change is a broad legislative push for age verification. Newly minted laws in 25 U.S. states and at least a dozen countries now demand that site operators verify the age of their users before displaying “inappropriate” content.

Many of these laws were designed to block pornography, but (exactly as many civil liberties folks warned) the practical effect is to implement new identity checks on almost every site that hosts user-supplied content. Age-verification checks are now popping up on social media websites like Facebook, BlueSky, X and Discord, and even the encyclopedia isn’t safe: for example, Wikipedia is slowly losing a fight to keep users identity private in the face of the U.K.’s Online Safety Bill.

Whatever you think about age verification, it’s obvious that routine ID checks will create a huge new privacy concern across the Internet. Users of most sites will need to identify themselves, not by pseudonym but using actual government ID. Implemented poorly, this could create a citizen-level transcript of everything you do online. While some nations’ age-verification laws seem aware of this — and allow privacy-conscious sites to voluntarily discard the information once they’ve processed it — this is not required, and far from uniform. Even when data minimization is permitted, advertising-supported sites will be an enormous financial incentive to retain that real-world identity information, since the value of precise human identity is huge in a world full of non-monetizable AI-bots.

Thus, the question for today is: how do we live in a world with routine age-verification and human identification, without completely abandoning our privacy?

Anonymous credentials: authentication without identification

Back in the 1980s, a cryptographer named David Chaum caught a glimpse of our future, and didn’t much like it. Long before the web or smartphones existed, Chaum recognized that users would need to routinely present (electronic) credentials to live their daily lives. He also saw that this would have enormous negative privacy implications. To address life in that world, he proposed a new idea: the anonymous credential.

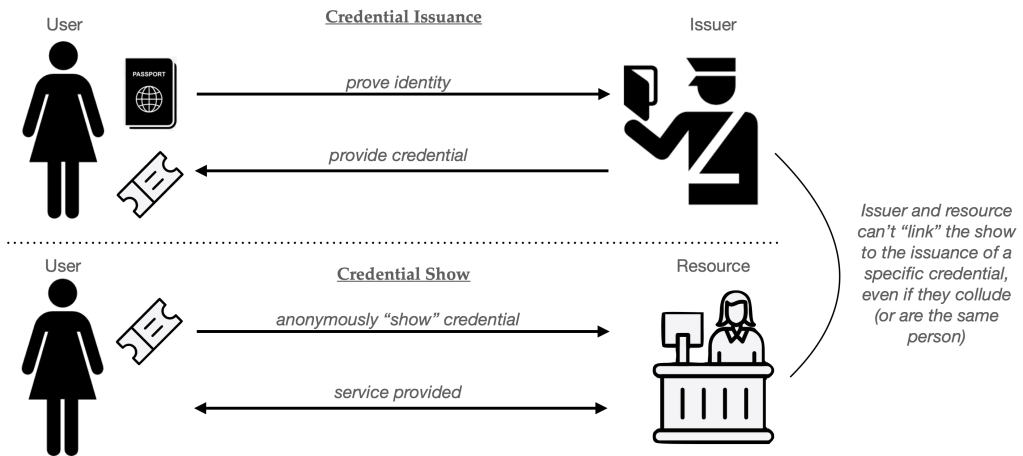

Chaum proposed the following model. Imagine a world where Alice needs to access some website or “Resource”. In a standard non-anonymous authentication flow, Alice must first be granted authorization (a “credential”, such as a cookie). This grant can come either from the Resource itself (e.g., the website), or in other cases, from a third party (for example, Google’s SSO service.) For the moment we’ll assume that this part of the process is not private: that is, Alice may need to reveal something about her real-world identity to the person who issues the credential. For example, she might use her credit card to pay for a subscription (e.g., for a news website), or she might hand over her driver’s license to prove that she’s an adult.

From a privacy perspective, the problem is that Alice will need to present her credential every time she wants to access any Resource that requires a credential. Concretely, each time she visits Wikipedia, she’ll need to hand over a credential that is tied to her real-world identity. A curious website (or an advertising network) can use that data to precisely link each visit to the site, tying all of them to her actual identity in the world. This is, to a much more limited extent, a version of the world we live in today: advertising companies probably know a lot about who we are and what we’re browsing. What’s about to change in our future is that these online identities will increasingly be bound to our names and government-issued ID, no more “Anonymous-User-38.”

Chaum’s idea was to break the linkage between the issuance and usage of that credential. When Alice shows her credential to the Resource (website), all it should learn is that some user has appeared with some valid credential. Critically, the Resource does not learn which specific user owns the credential, which means it should not be able to zero in on her exact ID. More importantly, this must hold even if the Resource colludes with (or literally is) the Issuer of the credential. The result is that, to the website, at least, Alice’s browsing is completely unlinked from her identity, and she can “hide” within the anonymity set of all users who obtained credentials.

One popular analogy for Chaum’s anonymous credentials is to think of them as a digital version of a “wristband”, the kind you might receive at the door of a club. You first show your ID to a person at the door, who then gives you an unlabeled wristband that indicates “this person is old enough to buy alcohol” or something along these lines. When you reach the bar, the bartender knows you only as the owner of a wristband and never needs to see your license. In principle your specific bar orders (for example, your love of spam-based drinks) is not somewhat untied from information like your actual name and address.

Why don’t we just give every user a copy of the same credential?

Before we get into the weeds of building anonymous credentials, it’s worth considering an obvious solution. What we want is simple: every user’s credential should be indistinguishable when “shown” to the Resource. The obvious question is: why doesn’t the the issuer give a copy of the exact same exact credential to every User? In principle this should solve all the privacy problems, since every user’s “show” will literally be identical. (In fact, this is more or less the digital analog of the physical wristband approach.)

The problem here is that digital items are fundamentally different from physical ones. Real-world items like physical credentials (even cheap wristbands) are at least somewhat difficult to copy. A digital credential, on the other hand, can be duplicated effortlessly. Imagine a hacker breaks into your computer and steals a single credential: they can now make an unlimited number of copies and use them to power a basically infinite army of bot accounts, or sell them to underage minors, all of whom will appear identical to the Resource that checks them.

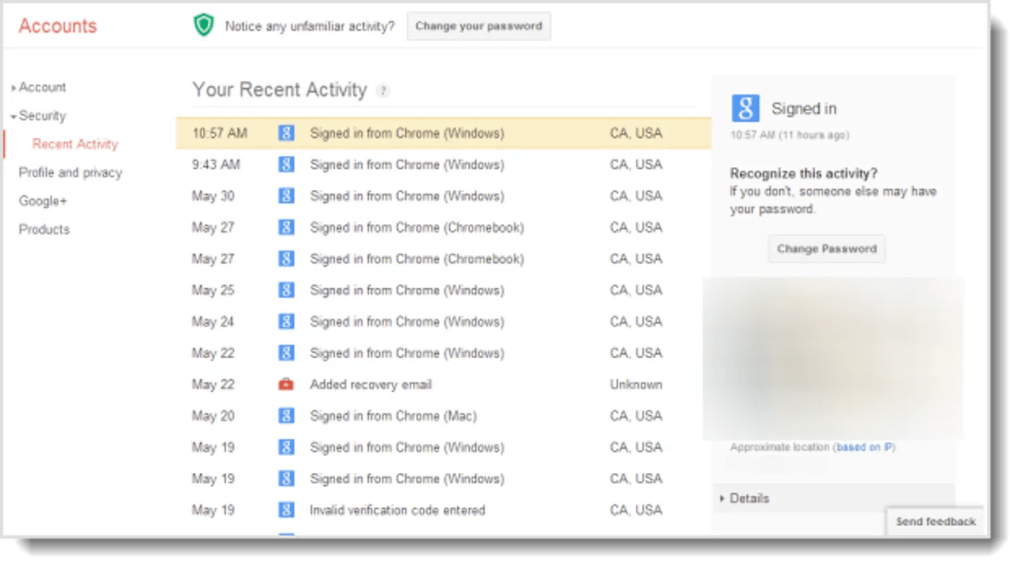

Of course, this exact same problem can occur with non-anonymous credentials, like usernames and session cookies. However, in the non-anonymous setting, credential cloning and other similar abuse can be detected, at least in principle. Websites routinely monitor for patterns that indicate the use of stolen credentials: for example, many will flag when they see a single “user” showing up too frequently, or from different and unlikely parts of the world, a procedure that’s sometimes called continuous authentication. Unfortunately, the anonymity properties of anonymous credentials render those checks ineffective, since every credential “show” looks like every other, and the site will have no idea if they’re all the same cloned credential or a bunch of different ones.

To address cloning, any real-world useful anonymous credential system requires some mechanism to limit credential duplication. The most basic approach is to provide users with credentials that are limited in some fashion. There are a few different approaches to this:

- Single-use (or limited-usage) credentials. The most common approach is to issue credentials that allow the user to log in (“Show” the credential) exactly one time. If a user wants to access the Resource fifty times, then she’ll need to obtain fifty separate credentials from the Issuer. A hacker may steal her credentials, but the hacker will then be limited to fifty website accesses. This approach is used by credentials like PrivacyPass, which is used by platforms like CloudFlare.

- Revocable credentials. Although this is slightly orthogonal, a different approach is to build credentials that can be revoked in the event of bad behavior. This requires a procedure such that when a particular anonymous user does something bad (posts spam, runs a DOS attack against a website) you can revoke that credential — blocking future usage of it (and all its clones).

- Hardware-tied credentials. Some industry proposals like Google’s new anonymous credential library “bind” credentials to a piece of hardware, such as the trusted platform module in your phone. This makes credential theft harder — a hacker will need to “crack” the hardware platform to clone a credentials. But a successful crack still has huge consequences that can undermine the security of the whole system.

The anonymous credential literature is filled with variants of the above approaches, sometimes combinations of the three. In every case, the goal is to put some barriers in the way of credential cloning.

Building a single-use credential

With these warnings in mind, we’re now ready to talk about how anonymous credentials are constructed. We’re going to discuss two different paradigms, which sometimes mix together to produce more interesting combinations.

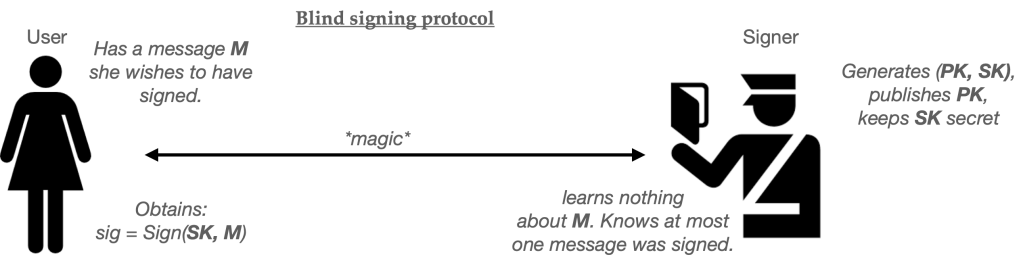

Chaum’s original proposal produced single-use credentials, and used an underlying primitive known as a blind signature scheme. Blind signatures are a version of digital signatures that feature an additional protocol that allows for “blind signing”. In this flow, a User has a message they want to have signed, while the Server holds the secret half of a public/secret signing keypair. The two parties run an interactive protocol, at the conclusion of which the User obtains a signature on their message. The server knows that it signed exactly one message, but critically, does not learn the value of the message that it signed.

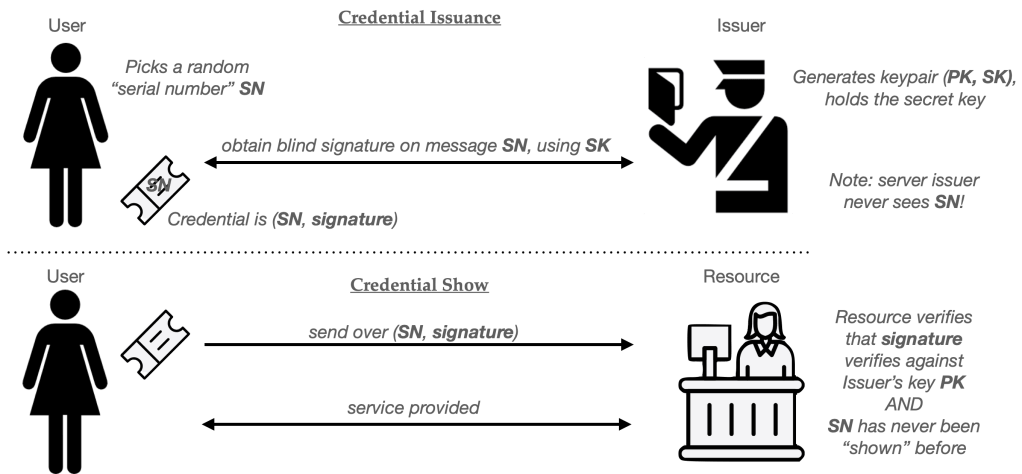

For the purposes of this post, we won’t spend much time building blind signatures (though some more details are here, if you’re interested.) Let’s just assume we’ve been handed a working blind signature scheme. Using this scheme as our base ingredient, we can build a basic single-use anonymous credential as follows:

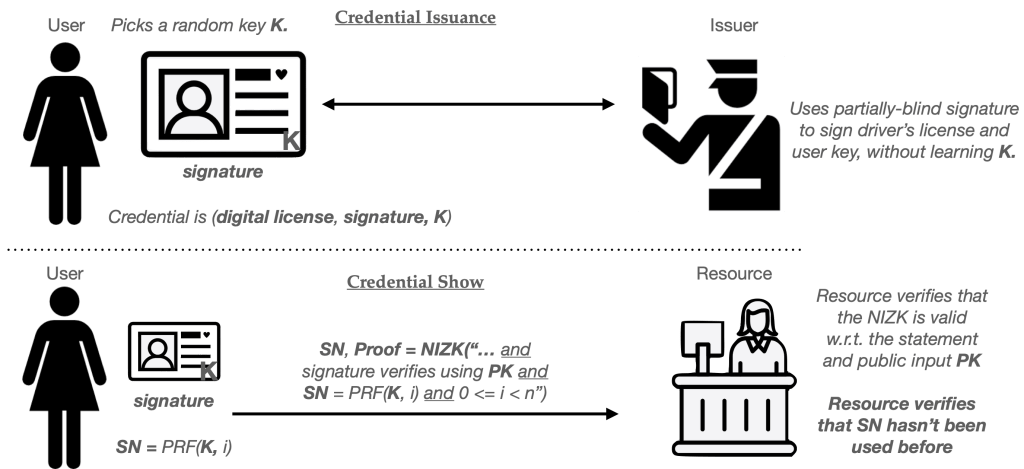

- At setup time, the Issuer generates a signing keypair (PK, SK) and gives out the key PK to everyone who might wish to verify its signatures. This keypair can be used to issue many credentials.

- When the User wishes to obtain a credential, she randomly selects a new serial number SN. This random string must be long enough that the same number is unlikely to repeat during the usage of the system, assuming numbers are truly chosen at random.

- The User and Issuer next run the blind signing protocol described above. In this case, the User sets its message to SN and the Issuer employs its key SK as the signing key. At the completion of this protocol, the user will hold a valid signature under the Issuer’s key computed over the message “SN”. The pair (SN, signature) form the User’s credential.

To “show” the credential to some Resource, the User simply hands over the pair (SN, signature). Provided that the Resource knows the public key (PK) of the issuer, it can verify that (1) the signature is valid on message SN, and (2) nobody has used that specific value SN in some previous credential “show”.

If there is exactly one Resource (website) consuming these credentials, then serial number checking can be conducted locally, using a simple database of all past SN values. Things get a bit messier if there are many Resources (say different websites) that credentials can be used at. One solution is to outsource serial number checks to some centralized service (or “bulletin board”) which can prevent a user from re-using a single credential across many different sites.

Here’s the whole protocol in helpful pictograms:

Chaumian credentials are forty years old and the basic idea still works well enough, provided your Issuer is willing to bear the cost of running a blind signature protocol for each credential it issues, and that the Resource doesn’t mind verifying a signature every time you use one. Protocols like PrivacyPass actually realize this using ingredients like blind RSA signatures. (PrivacyPass also includes a separate variant called a “blind MAC” for cases where the Issuer and Resource are the same entity, which can make a big difference for performance.1)

Single-use credentials work well, but they aren’t without their drawbacks. The big ones are (1) efficiency, and (2) lack of expressiveness.

The efficiency issue becomes obvious when you consider a User who accesses a website site many times. For example, imagine using an anonymous credential to replace Google’s session cookies. For most users, this require obtaining and delivering thousands of single-use credentials every single day. You could mitigate this problem by using credentials only for the first registration to a specific website, after which you could trade your credential for a pseudonym issued by the site (such as a random username or a normal session cookie) which would reduce the need for credential usage. The downside of this is that all of your subsequent site accesses would be linkable, which is a bit of a tradeoff.

The expressiveness objection is a bit more complicated. Let’s talk about that next.

Let’s be expressive!

Simple Chaumian credentials have a more fundamental limitation: they don’t carry much information.

Consider our bartender in a hypothetical wristband-issuing club. When I show up at the door, I provide my ID and get a wristband that shows I’m over 21. In this scenario, we can say that the wristband carries “one bit” of information: namely, the fact that you’re older than some arbitrary age constant.

Sometimes we want to do prove more complicated things with a digital credential. For example, imagine that I want to join a cryptocurrency exchange that needs more complicated assurances about my identity. For example: it might require that I’m a US resident, but not a resident of New York State (which has its own regulations.) The site might also demand that I’m over the age of 25. (I am literally making these requirements up as I go.) I could satisfy the website on all these fronts using the digitally-signed driver’s license issued by my state’s DMV. This is a real thing! It consists of a signed and structured document full of all sorts of useful information: my home address, state of issue, eye color, birthplace, height, weight, hair color and gender. In this world, the non-anonymous solution is easy: I can just hand over my entire digitally-signed license and the website can check the signature and verify the properties it needs.

The downside to handing over my driver’s license is that doing so also leaks much more information than the site requires. For example, this creepy website will also learn my home address, which it might use it to send me junk mail! It will learn that I’m a specific user, every time I show up with the same license. I’d really prefer it didn’t. A much better solution would allow me to assure the website only that I’ve satisfied the specific requirements that it cares about and nothing else.

In this example, everything I want to prove can be summarized in the following four bullet points:

- BIRTHDATE <= (TODAY – 25 years)

- ISSUE_STATE != NY

- ISSUE_COUNTRY = US

- SIGNATURE = (some valid signature that verifies under one of fifty known state DMV public keys.)

One obvious solution is that I could outsource all of these checks to some centralized Issuer (showing it my whole license), and have the Issuer now issue me a single-use “wristband” credential that claims that I satisfy all these requirements. This requires trusting some third-party Issuer with all of the information on my license, and also means that I’ll have to visit the Issuer every time I want to log into the website.

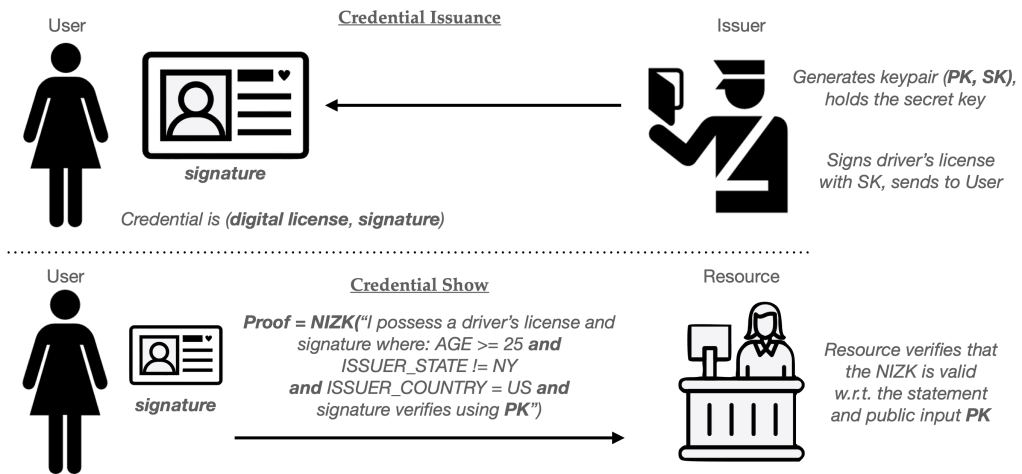

An alternative way to accomplish this is to use a zero-knowledge (ZK) proof. ZK proofs allows a party (called a Prover) to prove that they know some secret value that satisfies various constraints. For example, I could use a ZK proof to convince a Resource that I possess a signed, structured driver’s license credential. I could further use the proof to demonstrate that the value in the specific fields referenced above satisfies the necessary constraints. The lovely thing about using a ZK proofs for this task is that the website should be entirely convinced that I truly possess a valid driver’s license, and yet the zero-knowledge property ensures that I reveal nothing at all beyond the fact that these claims are true.

A variant of the ZK proof, called the non-interactive zero-knowledge proof (NIZK) lets me do this in a single message from User to Issuer. Using this tool, I can build a credential system as follows:

(These zero-knowledge techniques are ridiculously powerful. Not only can I change the constraints I’m asserting, but I can also perform proofs that reference multiple different credentials at the same time. For example, I might prove that I have a driver’s license, and also that by digitally-signed credit report indicates that I have a credit rating over 700.)

The zero-knowledge approach conveniently also addresses the efficiency limitation of the basic single-use credential. This is because the same credential (driver’s license) can now be re-used to power many “show” protocol runs, without allowing websites to link any credential “show” to the others. This guarantee stems from the fact that ZK proofs are genuinely reveal no information to the user, even the minimal fact that two different shows are the same user.2

Of course, there are downsides to this re-usability as well, as we’ll discuss in the next section.

How to win the clone wars

We’ve argued that the zero-knowledge paradigm has two advantages over simple Chaumian credentials. First, it’s potentially much more expressive. Second, it allows a User to re-use a single credential many times without needing to constantly retrieve more single-use credentials from the Issuer. While that last fact is very convenient, it raises a concern we already mentioned: what happens if a hacker steals one of these re-usable driver’s license credentials?

This is catastrophic for anonymous credential systems, since any single stolen credential can be cloned an unlimited number of times, basically without detection. It’s even worse in the real-world where you have millions of users, because the “hacker” in this case might be one of your legitimate customers!

As I noted above, one possible solution is to make credential theft very, very hard. This is the optimistic approach suggested in Google’s new anonymous credential scheme. Here, credentials will be tied to a secret key stored within the “secure element” in your phone, which theoretically makes the credential hard to duplicate onto a different device. The problem with this approach is that it requires an amazing amount of security across a vast number of phones. There are hundreds of millions of Android phones in the world, and the Secure Element technology in them runs the gamut from “actually very good” (for high-end, flagship phones) to “kinda garbage” (for the cheapest burner Android phone you can buy at Target.) Unfortunately, anonymous credential systems don’t care about the best device in your ecosystem — they collapse when the worst ones are compromised. Putting this differently, basic systems can be highly fragile: a failure in any of those phones potentially compromises the integrity of the whole system.

This necessitates some alternative techniques that will limit the usefulness of a given credential. Once you have ZK proofs in place, there are many ways to do this.

One clever approach is to place a fixed limit on the number of times that a single ZK credential can be “used”. For example, imagine that the Issuer produces a credential can be “shown” at most N times before it expires. This is much the same as requiring the user to extract N single-use credentials, but with much less work.

We can modify our ZK credential to support this limit as follows: First, have the User select a random key K for a pseudorandom function (PRF), and insert it into the credential to be signed. This function is somewhat like a good hash function: it’s a deterministic function that takes in a key and an arbitrary “message”, then blends them to produce a random-looking output that should be unlikely to repeat, provided the same message is not re-evaluated. Once K is embedded into the credential, we’ll have the issuer sign it. (It’s important that the Issuer does not learn K, so this often requires that the credential be signed using a blind, or partially-blind, signing protocol.3) We’ll now use this key and PRF to generate unique serial numbers, one for each time we “show” the credential.

Concretely, the ith time we “Show” the credential, the User will compute a “serial number” as follows:

SN = PRF(K, i)

Once the User has computed SN for a particular show, it sends this serial number to the Resource along with the zero-knowledge proof. The ZK proof will, in turn, be modified to include two additional clauses:

- A proof that SN = PRF(K, i), for some counter value i, and that K is the key that’s stored within the signed credential.

- A proof that 0 <= i < N.

Notice that these “serial numbers” work very much like the ones from our single-use credentials up above. Every Resource (website) must keep a list of all the SN values that it sees, and it can use this to reject any “show” that repeats a serial number. As long as the User never repeats a counter value i (and the PRF output is long enough to avoid collisions), honest users should not run into repeated serial numbers. However, a user who “cheats” and tries to show the same credential N+1 times will always have to repeat a serial number, and their “show” cheating will be detected.

This basic approach has many variants. For example, with only simple tweaks, can build credentials that only permit the User to employ the credential a limited number of times in any given time period: for example, at most 100 times per day.4 This requires us to simply change the inputs to the PRF function, so that the “message” is “(current_date, i)” rather than just i. Because the date changes every day, the same input will only occur if the user repeats i too many times within a single day. These techniques are described in a great paper whose title I’ve stolen for this section.

Expiring and revoking credentials

The power of the zero-knowledge techniques supplies us with many other tools to limit the power of credentials. For example, it’s easy to add expiration dates to credentials. This will implicitly limit their useful lifespan, and hopefully reduce the probability that one gets stolen. To do this, we simply add a new field (e.g., Expiration_Time) to the credential, and embed a timestamp at which the credential should expire.

Whenever a user “shows” the credential, they can first check their system clock for the current time T, and can add one more clause to their ZK proof:

T < Expiration_Time

Revoking credentials is only a bit more complicated.

One of the most important countermeasures against credential abuse is the ability to ban users who behave badly. This sort of revocation happens all the time on real sites: for example, when a user posts spam on a website, or abuses the site’s terms of service. Yet implementing revocation with anonymous credentials seems implicitly difficult. In a non-anonymous credential system we simply identify the user and add them to a banlist. But anonymous credential users are anonymous! How do you ban a user who doesn’t have to identify themselves?

That doesn’t mean that revocation is impossible. In fact, there are several clever tricks for banning credentials in the zero-knowledge credential setting.

Imagine we’re using a basic signed credential like the one we’ve previously discussed. As in the constructions above, we’re going to ensure that the User picks a secret key K to embed within the signed credential.5 As before, the key K will power a pseudorandom function (PRF) that can make pseudorandom “serial numbers” based on some input.

For the moment, let’s assume that the site’s “banlist” is empty. When a user goes to authenticate itself, the User and website interact as follows:

- First, the website will generate a unique/random “basename” bsn that it sends to the User. This is different for every credential show, meaning that no two interactions should ever repeat a basename.

- The user next computes SN = PRF(K, bsn) and sends SN to the Resource, along with a zero-knowledge proof that SN was computed correctly.

If the user does nothing harmful, the website delivers the requested service and nothing further happens. However, if the User abuses the site, the Resource will now ban this User by adding the pair (bsn, SN) to the banlist.

Now that the banlist is non-empty, we require an additional step occur every time a subsequent User shows their credential: specifically, the User must prove to the website that they aren’t on the banlist. In practice, this requires the User to enumerate every pair (bsni, SNi) on the banlist, and prove that for each one, the following statement holds true:

SNi ≠ PRF(K, bsni) — (using the User’s key K from their credential).

Naturally this approach adds some work on the User’s part: if there are M users on the banned list, then every User must now prove about M extra statements when “showing” their credential, which isn’t ideal — but works as long as the number of banned users stays relatively small.

Up next: what do real-world credential systems look like?

So far we’ve just dipped our toes into the techniques that we can use for building anonymous credentials. This tour has been extremely shallow: we haven’t talked about how to build any of the pieces we need to make them work. We also haven’t addressed tough real-world questions like: where are these digital identity certificates coming from, and what do we actually use them for?

In the next part of the piece I’m going to try to make this all much more concrete, by looking at two real-world examples: PrivacyPass, and a brand-new proposal from Google to tie anonymous credentials to your driver’s license on Android phones.

(To be continued)

Headline image: Islington Education Library Service

Notes:

- PrivacyPass has two separate issuance protocols. One uses blind RSA signatures, which are more or less an exact mapping to the protocol we described above. The second one replaces the signature with a special kind of MAC scheme, which is built from an elliptic-curve OPRF scheme. MACs work very similarly to signatures, but require the secret key for verification. Hence, this version of PrivacyPass really only works in cases where the Resource and the Issuer are the same person, or where the Resource is willing to outsource verification of credentials to the Issuer.

- This is a normal property of zero-knowledge proofs, namely that any given “proof” should reveal nothing about the information proven on. In most settings this extends to even alowing the ability to link proofs to a specific piece of secret input you’re proving over, which is called a witness.

- A blind signature ensures that the server never learns which message it’s signing. A partially-blind signature protocol allows the server to see a part of the message, but hides another part. For example, a partially-blind signature protocol might allow the server to see the driver’s license data that it’s signing, but not learn the value K that’s being embedded within a specific part of the credential. A second way to accomplish this is for the User to simply commit to K (e.g., compute a hash of K), and store this value within the credential. The ZK statement would then be modified to prove: “I know some value K that opens the commitment stored in my credential.” This is pretty deep in the weeds.

- In more detail, imagine that the User and Resource both know that the date is “December 4, 2026”. Then we can compute the serial number as follows:

SN = PRF(K, date || i)

As long we keep the restriction that 0 <= i < N (and we update the other ZK clauses appropriately, so they ensure the right date is included in this input), this approach allows us to use N different counter values (i) within each day. Once both parties increment the date value, we should get an entirely new set of N counter values. Days can be swapped for hours, or even shorter periods, provided that both parties have good clocks. - In real systems we do need to be a bit careful to ensure that the key K is chosen honestly and at random, to avoid a user duplicating another user’s key or doing something tricky. Often real-world issuance protocols will have K chosen jointly by the Issuer and User, but this is a bit too technically deep for a blog post.