This is part 2 of a series on the Random Oracle Model. See “Part 1: An introduction” for the previous post.

In a previous post I promised to explain what the  Random Oracle Model is, and — more importantly — why you should care about it. I think I made a good start, but I realize that I haven’t actually answered either of these questions.

Random Oracle Model is, and — more importantly — why you should care about it. I think I made a good start, but I realize that I haven’t actually answered either of these questions.

Instead what I did is talk a lot about hash functions. I described what an ideal hash function would look like: namely, a random function. Then I spent most of the post explaining why random functions were totally impractical (recap: too big to store, too slow to compute).

At the end of it all, I left us with the following conclusions: random functions would certainly make great hash functions, but unfortunately we can’t use them in real life. Still, if we can’t get a security proof any other way, it might just be useful to pretend that a hash function can behave like a random function. Of course, when we actually deploy the scheme we’ll have to use a real hash function like SHA or RIPEMD — definitely not random functions — and it’s not clear what our proof would mean in that case.

Still, this isn’t totally useless. If we can accomplish such a security proof, we can at least rule out the “obvious” attacks (based on the kind of glitches that real scheme designers tend to make). Any specific attack on the scheme would essentially have to have something to do with the properties of the hash function. This is still a good heuristic.

As you can see, this has gotten somewhat technical, and it’s going to get a bit more technical through to the end of the post. If you’ve gotten enough background to get the gist of the thing, feel free to skip on to the next post in this series, in which I’ll talk about where this model is used (hint all modern RSA signing and encryption!), and what it means for cryptography in practice.

Brass tacks

A security proof typically considers the interaction of two or more parties, one of whom we refer to as the adversary. In a typical proof, most of the players are “honest”, meaning they’ll operate according to a defined cryptographic protocol. The adversary, on the other hand, can do anything she wants. Her goal is to break the scheme.

Usually we spell out a very specific game that the parties will play. For an encryption scheme, the rules of this game allow the adversary to do things that she might be able to do in a “real world” environment. For example: she might be able to obtain the encryption of chosen plaintexts and/or the decryption of chosen ciphertexts. In most cases she’ll intercept a legitimate ciphertext transmitted by an honest encryptor. Typically her goal is to learn (something about) the underlying plaintext.

It’s standard to assume that the parties will all know the scheme or protocol, including how to compute the hash function if one is used. This is a common-sense assumption, sometimes referred to as Kerckhoffs’s Principle. Moreover, we generally assume that the adversary is limited in some way — she doesn’t have unlimited computational power or time, which means she can’t just brute force the decryption key.

|

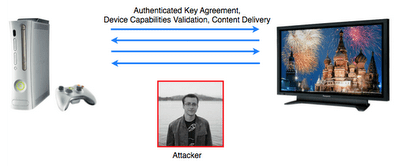

| Security proof in the random oracle model. All parties (Encryptor, Decryptor and Adversary) can call out to the Random Oracle, which computes the hash function for them and provides consistent responses to all parties. |

A Random Oracle security proof is just like this, but we make one further tweak. Even though everyone is allowed to compute the hash function, they can’t do it by themselves. Hashing is done by a new magical party called the “oracle”. If any party needs to hash something, they ship the message (over an imaginary secure channel) to the oracle, who computes the hash and sends it back to them.

Why the oracle? Well, since the oracle is “outside” of the parties, they no longer need to carry around a description of the hash function, and they don’t need to do the work of computing it. This is good because — as I mentioned in the previous post — the full description of a random function is ridiculously large, and consequently takes an insane of amount of time to compute. By sticking it into the oracle, we can handwave away that ugliness.

We’ll place two restrictions on the random oracle. First, it must implement a genuine random function (sampled at the beginning of the game), with the same input/output profile as a realistic hash function we might use (e.g., 256-bit output strings if we’re eventually going to implement with SHA256).

Secondly, the responses given by the oracle must be consistent. In other words, just as hashing “Peter Piper” through SHA1 will always produce 1c6244929dc8216f5c1024eebefb5cb73c378431,* regardless of who does it, sending a given string through the random oracle will produce the same result, regardless of which party asks for it.

Lazy Afternoon

There’s one last (and kind of neat) trick related to how we model the Random Oracle. Internally a random oracle just implements a huge table mapping input values to random output strings. Since this is the case, our security proofs can fill this table in “lazily”. Rather than starting with an entire table all filled in, we can instead begin our analysis with an empty table, and generate it as we go. It works like this:

- At the beginning of the game the oracle’s table is empty.

- Whenever some party asks the oracle to hash a message, the oracle first checks to see if that input value is already stored in the table.

- If not, it generates a random output string, stores the input message and the new output string in its table, and returns the output string to the caller.

- If the oracle does find the input value in the table, it returns output value that’s already stored there.

If you think about this for a minute, you’ll realize that, to the various parties, this approach “looks” exactly the same as if the oracle had begun with a complete table. But it makes our lives a little easier.

Back to Delphia

In the last post I proposed to build a

stream cipher out of a hash function H(). To get a little bit more specific, here’s a version of what that algorithm might look like:

1. Pick a random secret key (say 128 bits long) and share it with both the sender and receiver.

Set IV to 1.

2. Cut a plaintext message into equal-length blocks M1, …, MN,

where every block is exactly as long as the output of the hash function.

3. Using || to indicate concatenation and ⊕ for exclusive-OR, encrypt the message as follows:

C1 = H(key || IV) ⊕ M1

C2 = H(key || IV+1) ⊕ M2

…

CN = H(key || IV+N) ⊕ MN

4. Output (IV, C1, C2, ..., CN) as the ciphertext.

5. Make sure to set IV = (IV+N+1) before we encrypt the next message.

If you’re familiar with the modes of operation, you might notice that this scheme looks a lot like

CTR mode encryption, except that we’re using a hash function instead of a block cipher.

A proof sketch!

Let’s say that I want to prove that this scheme is secure in the Random Oracle Model. Normally we’d use a specific definition of “secure” that handles many things that a real adversary could do. But since this is a blog, we’re going to use the following simplified game:

Some honest party — the encryptor — is going to encrypt a message. The adversary will intercept the ciphertext. The adversary “wins” if he can learn any information about the underlying plaintext besides its length.

Recall that we’re in the magical Random Oracle Model. This is just like the real world, except whenever any party computes the hash function H(), s/he’s actually issuing a call out to the oracle, who will do all the work of hashing using a random function. Everyone can call the oracle, even the adversary.

Following the scheme description above, the encryptor first chooses a random key (step 1). He divides his plaintext up into blocks (step 2). For each block i = 1 to N, he queries the oracle to obtain H(key || i). Finally, he XORs the received hashes with the blocks of the plaintext (step 3), and sends the ciphertext (C1, …, CN) out such that the adversary intercepts it (step 4).

We can now make the following observations.

- Internally, the oracle starts with an empty table.

- Each time the oracle receives a new query of the form “key || i” from the encryptor, it produces a new, perfectly random string for the output value. It stores both input and output in its table, and sends the output back to the encryptor.

- The encryptor forms the ciphertext blocks (C1, …, CN) by XORing each message block with one of these random strings.

- The encryptor never asks for the same input string twice, because the IV is always incremented.And finally, we make the most important observation:

- XORing a message with a secret, perfectly random string is a very effective way to encrypt it. In fact, it’s a One Time Pad. As long as the adversary does not know the random string, the resulting ciphertext is itself randomly-distributed, and thus reveals no information about the underlying message (other than its length).

Based on observation (5), all we have to do is show that the values returned when the oracle hashes “key || i” are (a) each perfectly random, and (b) that the adversary does not learn them. If we can do this, then we’re guaranteed that the ciphertext (C1, …, CN) will be a random string, and the adversary can learn nothing about the underlying plaintext!

The Final Analysis

Demonstrating part (a) from above is trivial. When the encryptor asks the oracle to compute H(key || i), provided that this value hasn’t been asked for previously, the oracle will generate a perfectly random string — which is all spelled out in the definition of how the oracle works. Also, the encryptor never asks for the same input value twice, since it always updates its IV value.

Part (b) is a little harder. Is there any way the Adversary could learn the oracle’s output for H(key || i) for even one value of i from 1 to N? The oracle does not make its table public, and the adversary can’t “listen in” on the hash calls that the encryptor made.

Thinking about this a little harder, you’ll realize that there’s exactly one way that the adversary could learn one of those strings: she can query the oracle too. Specifically, all she has to do is query the oracle on “key || i” for any 1 <= i <= N and she’ll get back one of the strings that the encryptor used to encrypt the ciphertext. If the adversary learns one of these strings, she can easily recover (at least part of) the plaintext, and our argument doesn’t work anymore.

There’s one obvious problem with this, at least from the adversary’s point of view: she doesn’t know the key.

So in order to query on “key || i”, the adversary would have to guess the key. Every time she submits a guess “guess || i” to the oracle she’ll either be wrong — in which case she gets back a useless random string. Or she’ll be right, in which case our scheme won’t be secure anymore.

But fortunately for us, the key is random, and quite big (128 bits). This tells us something about the adversary’s probability of success.

Specifically: if she makes exactly one guess, her probability of guessing the right key is quite small: one in the number of possible keys. For our specific example, her success probability would be 1/(2^128), which is astronomically small. Or course, she could try guessing more than once; if makes, say q guesses, her success probability rises to q/(2^128).

The basic assumption we started with is that the adversary is somehow limited in her computational power. This means she can only perform a reasonable number of hashes. In a formal security proof this is where we might invoke polynomial vs. exponential time. But rather than do that, let’s just plug in some concrete numbers.

Let’s assume that the adversary only has time to compute 2^40 (1.1 trillion) hashes. Assuming we used a 128-bit key, then her probability of guessing the key is at most (2^40)/(2^128) = 1/(2^88). This is still a pretty tiny number.

Think a real-world adversary might be able to compute more than 2^40 hashes? No problem. Plug in your own numbers — the calculation stays the same. And if you think the scheme isn’t secure enough, you can always try making the key longer.

The point here is that we’ve demonstrated that in the Random Oracle Model the above scheme is ‘as secure as the key’.** In other words, the adversary’s best hope to attack the scheme is to find the key via brute-force guessing. As long as the key is large enough, we can confidently conclude that a “realistic” (i.e., time-bounded) adversary will have a very low — or at least calculable — probability of learning anything about the message.

In Summary

Depending on your point of view, this may have seemed a bit technical. Or maybe not. In any case, it definitely went a bit past the “layperson’s introduction” I promised in the previous post. Moreover, it wasn’t technical enough, in that it didn’t capture all of the ways that cryptographers can “cheat” when using the random oracle model.***

I’m going to do my best to up for that in the next post, where we’ll talk a bit about some real schemes with proofs in the random oracle model, and — more importantly — why cryptographers are willing to put up with this kind of thing.

See the next post: Part 3, in which the true nature of the Random Oracle Model is revealed.

Notes:

* I got this result from an online SHA1 calculator of untrusted veracity. YMMV.

** Of course, in a real proof we’d be more formal, and we’d also consider the possibility that an adversary might at least be able to obtain the encryption of some chosen plaintexts. This would be captured in the security game we use.

*** Some will note that I didn’t exactly need to model the hash function as a random oracle to make this example work. Had I invoked a keyed hash function, I might have used a weaker assumption (and in this case, weak is good!) that H() is pseudo-random. But this is really a topic for another post. I chose this example for pedagogical reasons (it’s easy to understand!) rather than its unique need for a random oracle analysis.

Oswald and Christof Paar’s recent

Oswald and Christof Paar’s recent

provable security, and something called the “Random Oracle Model”. While getting my thoughts together, it occurred to me that a) this subject might be of interest to people who aren’t my grad students, and b) there doesn’t seem to be a good “layperson’s” introduction to it.For the most part I like to talk about how cryptography gets implemented. But implementation doesn’t matter a lick if you’re starting with insecure primitives.

provable security, and something called the “Random Oracle Model”. While getting my thoughts together, it occurred to me that a) this subject might be of interest to people who aren’t my grad students, and b) there doesn’t seem to be a good “layperson’s” introduction to it.For the most part I like to talk about how cryptography gets implemented. But implementation doesn’t matter a lick if you’re starting with insecure primitives.