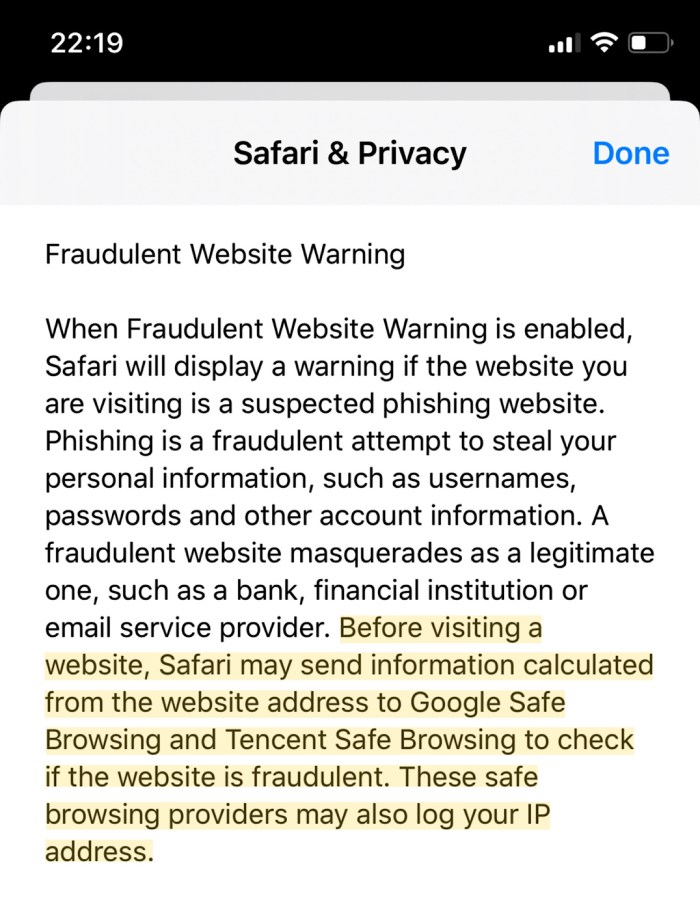

This morning brings new and exciting news from the land of Apple. It appears that, at least on iOS 13, Apple is sharing some portion of your web browsing history with the Chinese conglomerate Tencent. This is being done as part of Apple’s “Fraudulent Website Warning”, which uses the Google-developed Safe Browsing technology as the back end. This feature appears to be “on” by default in iOS Safari, meaning that millions of users could potentially be affected.

As is the standard for this sort of news, Apple hasn’t provided much — well, any — detail on whose browsing history this will affect, or what sort of privacy mechanisms are in place to protect its users. The changes probably affect only Chinese-localized users (see Github commits, courtesy Eric Romang), although it’s difficult to know for certain. However, it’s notable that Apple’s warning appears on U.S.-registered iPhones.

Regardless of which users are affected, Apple hasn’t said much about the privacy implications of shifting Safe Browsing to use Tencent’s servers. Since we lack concrete information, the best we can do is talk a bit about the technology and its implications. That’s what I’m going to do below.

What is “Safe Browsing”, and is it actually safe?

Several years ago Google noticed that web users tended to blunder into malicious sites as they browsed the web. This included phishing pages, as well as sites that attempted to push malware at users. Google also realized that, due to its unique vantage point, it had the most comprehensive list of those sites. Surely this could be deployed to protect users.

The result was Google’s “safe browsing”. In the earliest version, this was simply an API at Google that would allow your browser to ask Google about the safety of any URL you visited. Since Google’s servers received the full URL, as well as your IP address (and possibly a tracking cookie to prevent denial of service), this first API was kind of a privacy nightmare. (This API still exists, and is supported today as the “Lookup API“.)

To address these concerns, Google quickly came up with a safer approach to, um, “safe browsing”. The new approach was called the “Update API”, and it works like this:

- Google first computes the SHA256 hash of each unsafe URL in its database, and truncates each hash down to a 32-bit prefix to save space.

- Google sends the database of truncated hashes down to your browser.

- Each time you visit a URL, your browser hashes it and checks if its 32-bit prefix is contained in your local database.

- If the prefix is found in the browser’s local copy, your browser now sends the prefix to Google’s servers, which ship back a list of all full 256-bit hashes of the matching URLs, so your browser can check for an exact match.

At each of these requests, Google’s servers see your IP address, as well as other identifying information such as database state. It’s also possible that Google may drop a cookie into your browser during some of these requests. The Safe Browsing API doesn’t say much about this today, but Ashkan Soltani noted this was happening back in 2012.

It goes without saying that Lookup API is a privacy disaster. The “Update API” is much more private: in principle, Google should only learn the 32-bit hashes of some browsing requests. Moreover, those truncated 32-bit hashes won’t precisely reveal the identity of the URL you’re accessing, since there are likely to be many collisions in such a short identifier. This provides a form of k-anonymity.

The weakness in this approach is that it only provides some privacy. The typical user won’t just visit a single URL, they’ll browse thousands of URLs over time. This means a malicious provider will have many “bites at the apple” (no pun intended) in order to de-anonymize that user. A user who browses many related websites — say, these websites — will gradually leak details about their browsing history to the provider, assuming the provider is malicious and can link the requests. (Updated to add: There has been some academic research on such threats.)

And this is why it’s so important to know who your provider actually is.

What does this mean for Apple and Tencent?

That’s ultimately the question we should all be asking.

The problem is that Safe Browsing “update API” has never been exactly “safe”. Its purpose was never to provide total privacy to users, but rather to degrade the quality of browsing data that providers collect. Within the threat model of Google, we (as a privacy-focused community) largely concluded that protecting users from malicious sites was worth the risk. That’s because, while Google certainly has the brainpower to extract a signal from the noisy Safe Browsing results, it seemed unlikely that they would bother. (Or at least, we hoped that someone would blow the whistle if they tried.)

But Tencent isn’t Google. While they may be just as trustworthy, we deserve to be informed about this kind of change and to make choices about it. At very least, users should learn about these changes before Apple pushes the feature into production, and thus asks millions of their customers to trust them.

We shouldn’t have to read the fine print

When Apple wants to advertise a major privacy feature, they’re damned good at it. As an example: this past summer the company announced the release of the privacy-preserving “Find My” feature at WWDC, to widespread acclaim. They’ve also been happy to claim credit for their work on encryption, including technology such as iCloud Keychain.

But lately there’s been a troubling silence out of Cupertino, mostly related to the company’s interactions with China. Two years ago, the company moved much of iCloud server infrastructure into mainland China, for default use by Chinese users. It seems that Apple had no choice in this, since the move was mandated by Chinese law. But their silence was deafening. Did the move involve transferring key servers for end-to-end encryption? Would non-Chinese users be affected? Reporters had to drag the answers out of the company, and we still don’t know many of them.

In the Safe Browsing change we have another example of Apple making significant modifications to its privacy infrastructure, largely without publicity or announcement. We have learn about this stuff from the fine print. This approach to privacy issues does users around the world a disservice.

It increasingly feels like Apple is two different companies: one that puts the freedom of its users first, and another that treats its users very differently. Maybe Apple feels it can navigate this split personality disorder and still maintain its integrity.

I very much doubt it will work.

I stopped using Google products as much as possible. And Safari is now on my list of items to “sunset”.

It’s easy to disable this in Safari – Preferences -> Security -> Un-check “Fraudulent Sites” setting.

I hate the thoughts of the iOS environment, but some of my favorite digital publications ONLY USE APPLE! After the latest iTunes exploit, I shudder to think about spending even the amount for a lowly iPad…I guess NOTHING is safe anymore, and the despised Android is AS SAFE as the iPhone or iPad…

Dude you’re like an unsung hero. I’m shocked at how many places covered this and didn’t like to you.

Ultimately it seems like you don’t understand hashing, k-anonymization or SHA256 as well as you think. Care to give some odds on the likelihood of Google or Tencent computing the actual URL being browsed from a 4 byte prefix of a SHA256 hash?

If they just hash the baseurl (i.e. google.com) I’d say it’s pretty easy. I mean what stops them to have a list of hashed “problematic” URLs to cross-reference with what you send to them? Ultimately you don’t really have to understand hashing, k-anonymization or SHA256 that well to come to this conclusion. lol

Not only will there likely be multiple URLs under the same prefix, but you might not be going to any of them, but instead some other, non-fraudulent URL that just happens to have the same hash prefix.

It’s the full URL that gets hashed, minus any credentials I believe.

They could have a list of problematic URLs, but that’s not what your browser sends them. If the very short hashed prefix matches, then the browser sends back just that hashed prefix and SB sends back a list of all hashed URLs that have the same prefix.

They could analyze all of the requests, but they only get requests from prefix matches, which means only a fraction of your overall sites visited. It’s almost certain that Google is doing such analysis and likely tencent is too. The API isn’t perfect but it’s difficult to see how else they could provide SB functionality…maybe a built in VPN with rotating IPs and aggressive anti-cookie/tracking measures. Cookies are the real danger for tracking in these cases.

Also strange is that the original blob post he posted to states that the privacy leak was Apple giving tencent user IP addresses. I almost choked on my coffee when I read that.

BTW, it would have been trivial to actually use your phone and test to see if iOS sent data to Tencent instead of speculating.

How would you test it on the iPhone? Are there apps (as in Android world)? I have several apps that are sending my data to Facebook, and I don’t have a Facebook Account!

Apple implied in the link you provided that only Chinese users were affected by the iCloud change, because Apple had to use a Chinese company to store the keys for any iCloud accounts used by Chinese citizens. I’ve seen no evidence that Apple moved any non-Chinese keys or non-Chinese user data to China.

Also, I think it’s preposterous to suggest that Tencent might be just as trustworthy as Google. The Chinese government is co-owner of Tencent, just as they are of all Chinese companies, and they have a penchant for spying and surveillance. No one concerned with privacy should ever do business with, or use any product or service of, a Chinese company.

Apple implied in the link you provided that only Chinese users were affected by the iCloud change, because Apple had to use a Chinese company to store the keys for any iCloud accounts used by Chinese citizens. I’ve seen no evidence that Apple moved any non-Chinese keys or non-Chinese user data to China.

Also, I think it’s preposterous to suggest that Tencent might be just as trustworthy as Google. The Chinese government is co-owner of Tencent, just as they are of all Chinese companies, and they have a penchant for spying and surveillance. No one concerned with privacy should ever do business with, or use any product or service of, a Chinese company.

1lmiAVD2

The tradeoff for privacy vs. security is probably worth it for most end-users. However, if Apple really wanted to go the extra mile and eliminate the controversy entirely they could simply proxy the requests through their own servers without logging them. So I think it’s fair to question their commitment to privacy here.

7XDhnSZGzvj