It’s not every day that we see mainstream media get excited about encryption apps! For that reason, the past several days have been fascinating, since we’ve been given not one but several unusual stories about the encryption used in WhatsApp. Or more accurately, if you read the story, a pretty wild allegation that the widely-used app lacks encryption.

This is a nice departure from our ordinary encryption-app fare on this blog, which mainly deals with people (governments, usually) claiming that WhatsApp is too encrypted.Since there have now been several stories on the topic, and even folks like Elon Musk have gotten into the action, I figured it might be good to write a bit of an explainer about it.

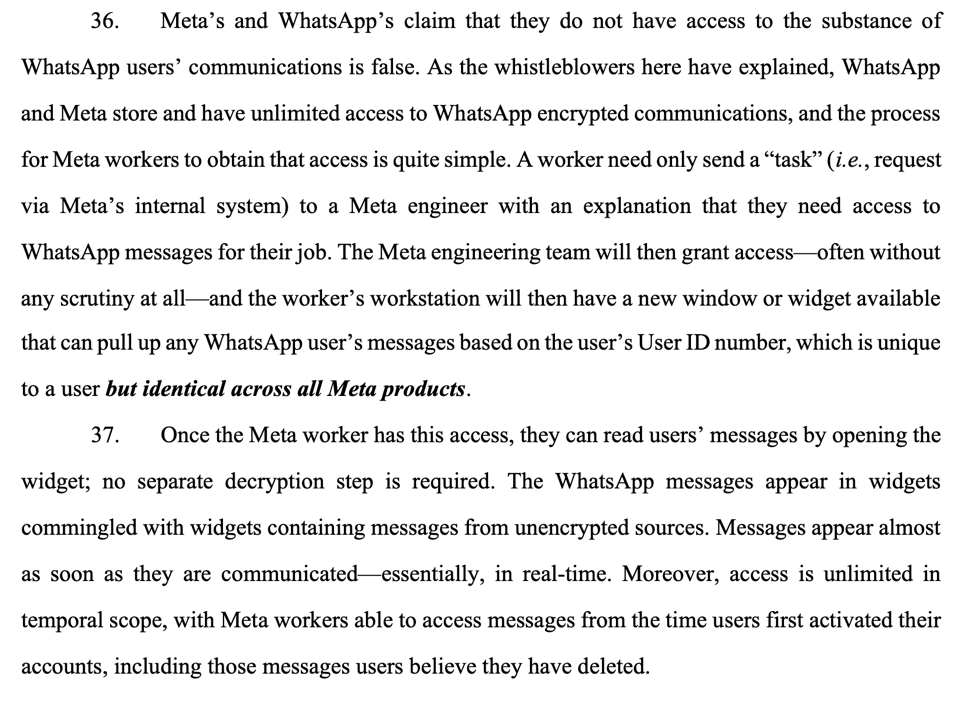

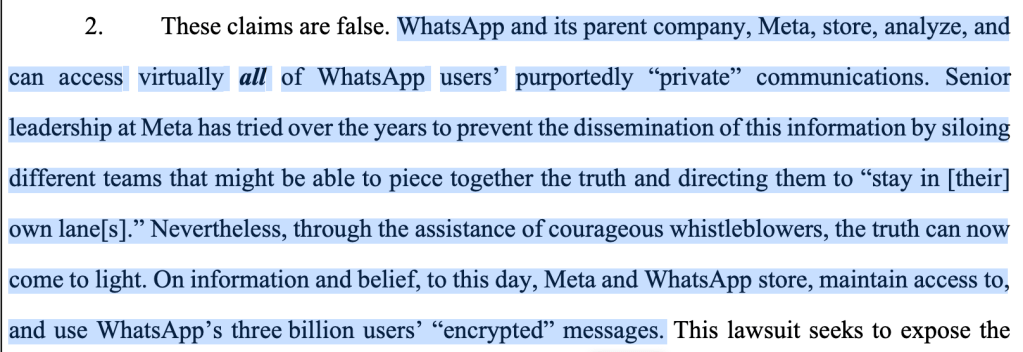

Our story begins with a new class action lawsuit filed by the esteemed law firm Quinn Emanuel on behalf of several plaintiffs. The lawsuit notes that WhatsApp claims to use end-to-end encryption to protect its users, but alleges that all WhatsApp users’ private data is secretly available through a special terminal on Mark Zuckerberg’s desk. Ok, the lawsuit does not say precisely that — but it comes pretty darn close:

The complaint isn’t very satisfying, nor does it offer any solid evidence for any of these claims. Nonetheless, the claims have been heavily amplified online by various predictable figures, such as Elon Musk and Pavel Durov, both of whom (coincidentally) operate competing messaging apps. Making things a bit more exciting, Bloomberg reports that US authorities are now investigating Meta, the owner of WhatsApp, based on these same allegations. (How much weight you assign to this really depends on what you think of the current Justice Department.)

If you’re really looking to understand what’s being claimed here, the best way to do it is to read the complaint yourself: you can find it here (PDF). Alternatively, you can save yourself a lot of time and read the next five sentences, which contain pretty much the same amount of factual information:

- The plaintiffs (users of WhatsApp) have all used WhatsApp for years.

- Through this entire period, WhatsApp has advertised that it uses end-to-end encryption to protect message content, specifically, through the use of the Signal encryption protocol.

- According to unspecified “whistleblowers”, since April 2016, WhatsApp (owned by Meta) has been able to read the messages of every single user on its platform, except for some celebrities.

Here’s the nut of it:

The Internet has mostly divided itself into people who already know these allegations are true, because they don’t trust Meta and of course Meta can read your messages — and a second set of people who also don’t trust Meta but mostly think this is unsupported nonsense. Since I’ve worked on end-to-end encryption for the last 15+ years, and I’ve specifically focused on the kinds of systems that drive apps like WhatsApp, iMessage and Signal, I tend to fall into the latter group. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to pay attentionto here.

Hence: in this post I’m going to talk a little bit about the specifics of WhatsApp encryption; what an allegation like this would imply (technically); we can verify that things like this are true (or not verify, as the case may be). More generally I’ll try to add some signal to the noise.

Full disclosure: back in 2016 I consulted for Facebook (now Meta) for about two weeks, helping them with the rollout of encryption in Facebook Messenger. From time to time I also talk to WhatsApp engineers about new features they’re considering rolling out. I don’t get paid for doing this; they once asked me if I’d consider signing an NDA and I told them I’d rather not.

Background: what’s end-to-end encryption, and how does WhatsApp claim to do it?

Instant messaging apps are pretty ancient technology. Modern IM dates from the 1990s, but the basic ideas go back to the days of time sharing. Only two major things have really changed in messaging apps since the days of AOL Instant Messenger: the scale, and also the security of these systems.

In terms of scale, modern messaging apps are unbelievably huge. At the start of the period in the lawsuit, WhatsApp already had more than one billion monthly active users. Today that number sits closer to three billion. This is almost half the planet. In many countries, WhatsApp is more popular than phone calls.

The downside of vast scale is that apps like this can also collect data at similarly large scale. Every time you send a message through an app like WhatsApp, you’re sending that data first to a server run by WhatsApp’s parent company, Meta. That server then stores it and eventually delivers it to your intended recipients. Without great care, this can result in enormous amounts of real-time message collection and long-term storage. The risks here are obvious. Even if you trust your provider, that data can potentially be accessed by hackers, state-sponsored attackers, governments, and anyone who can compel or gain access to Meta’s platforms.

To combat this, WhatsApp’s founders Jan Koum and Brian Acton took a very opinionated approach to the design of their app. Beginning in 2014 (around the time they were acquired by Facebook), the app began rolling out end-to-end (E2E) encryption based on the Signal protocol. This design ensures that all messages sent through Meta/WhatsApp infrastructure are encrypted, both in transit and on Meta’s servers. By design, the keys required to decrypt messages exist only on a users’ device (the “end” in E2E), ensuring that even a malicious platform provider (or hacker of Meta’s servers) should never be able to read the content of your messages.

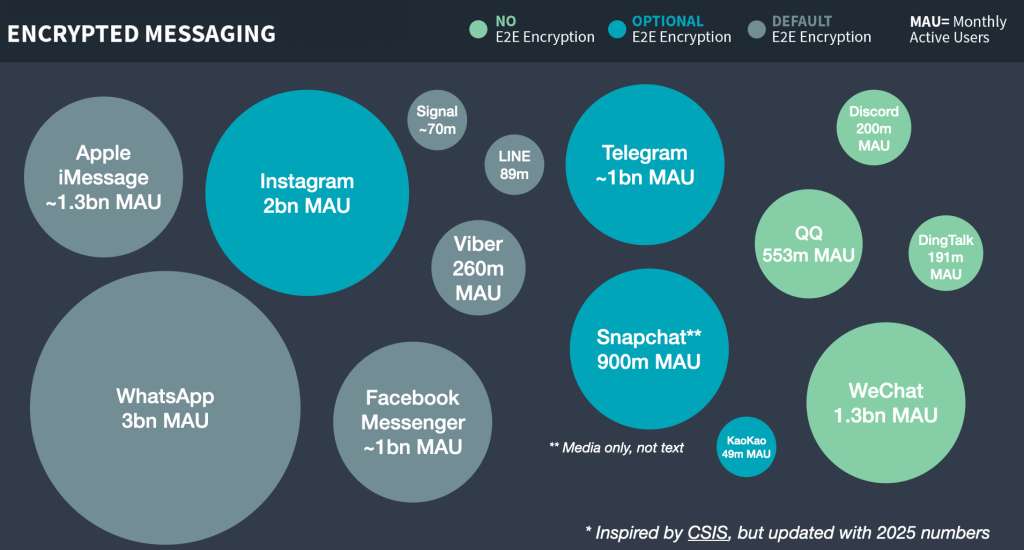

Due to WhatsApp’s huge scale, the adoption of end-to-end encryption on the platform was a very big deal.

Not only does WhatsApp’s encryption prevent Meta from mining your chat content for advertising or AI training, the deployment of this feature made many governments frantic with worry. The main reason was that even law enforcement can’t access encrypted messages sent through WhatsApp (at least, not through Meta itself.). To the surprise at many, Koum and Acton made a convert of Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, who decided to lean into new encryption features across many of the company’s products, including Facebook Messenger and (optionally) Instagram DMs.

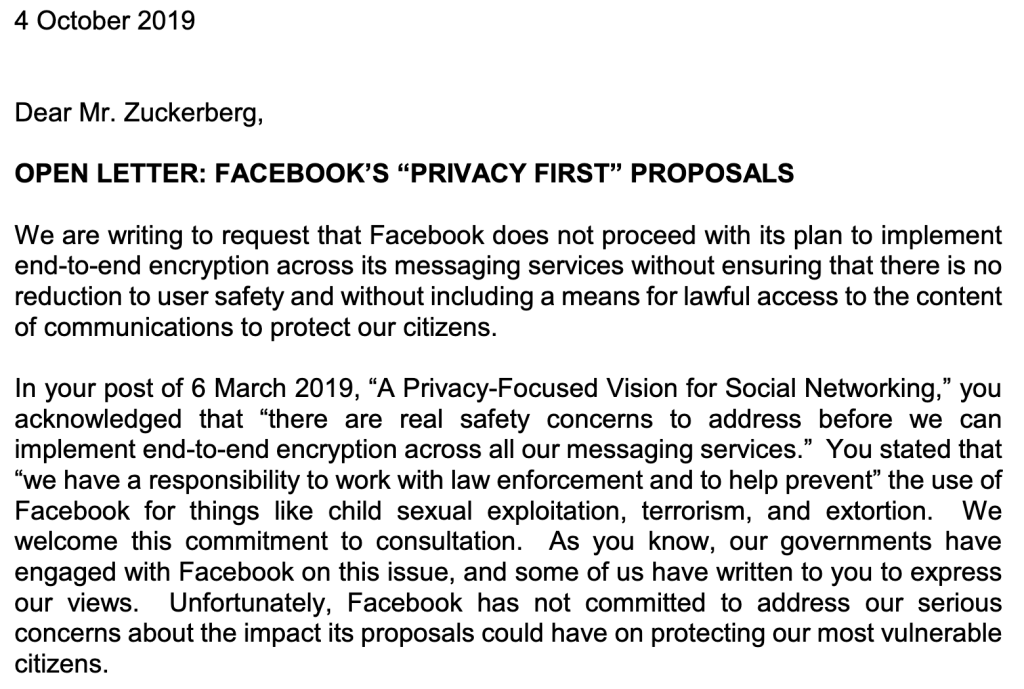

This decision is controversial, and making it has not been cost-free for Meta/Facebook. The deployment of encryption in Meta’s products has created enormous political friction with the governments of the US, UK, Australia, India and the EU. Each government is concerned about the possibility that Meta will maintain large numbers of messages they cannot access, even with a warrant. For example, in 2019 a multi-government “open letter” signed by US AG William Barr urged Facebook not to expand end-to-end encryption without the addition of “lawful access” mechanisms:

So that’s the background. Today WhatsApp describes itself as serving on the order of three billion users worldwide, and end-to-end encryption is on by default for personal messaging. They haven’t once been ambiguous about what they claim to offer. That means that if the allegations in the lawsuit proved to be true, this would be one of the largest corporate coverups since Dupont.

Are we sure WhatsApp is actually encrypted? Could there be a backdoor?

The best thing about end-to-end encryption — when it works correctly — is that the encryption is performed in an app on your own phone. In principle, this means that only you and your communication partner have the keys, and all of those keys are under your control. While this sounds perfect, there’s an obvious caveat: while the app runs on your phone, it’s a piece of software. And the problem with most software is that you probably didn’t write it.

In the case of WhatsApp, the application software is written by a team inside of Meta. This wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing if the code was open source, and outside experts could review the implementation. Unfortunately WhatsApp is closed-source, which means that you cannot easily download the source code to see if encryption performed correctly, or performed at all. Nor can you compile your own copy of the WhatsApp app and compare it to the version you download from the Play or App Store. (This is not a crazy thing to hope for: you actually can do those things with open-source apps like Signal.)

While the company claims to share its code with outside security reviewers, they don’t publish routine security reviews. None of this is really unusual — in fact, it’s extremely normal for most commercial apps! But it means that as a user, you are to some extent trusting that WhatsApp is not running a long-con on its three billion users. If you’re a distrustful, paranoid person (or if you’re a security engineer) you’d probably find this need for trust deeply unappealing.

Given the closed-source nature of WhatsApp, how do we know that WhatsApp is actually encrypting its data? The company is very clear in its claims that it does encrypt. But if we accept the possibility that they’re lying: is it at least possible that WhatsApp contains a secret “backdoor” that causes it to secretly exfiltrate a second copy of each message (or perhaps just the encryption keys) to a special server at Meta?

I cannot definitively tell you that this is not the case. I can, however, tell, you that if WhatsApp did this, they (1) would get caught, (2) the evidence would almost certainly be visible in WhatsApp’s application code, and (3) it would expose WhatsApp and Meta to exciting new forms of ruin.

The most important thing to keep in mind here is that Meta’s encryption happens on the client application, the one you run on your phone. If the claims in this lawsuit are true, then Meta would have to alter the WhatsApp application so that plaintext (unencrypted) data would be uploaded from your app’s message database to some infrastructure at Meta, or else the keys would. And this should not be some rare, occasional glitch. The allegations in the lawsuit state that this applied to nearly all users, and for every message ever sent by those users since they signed up.

Those constraints would tend to make this a very detectable problem. Even if WhatsApp’s app source code is not public, many historical versions of the compiled app are available for download. You can pull one down right now and decompile it using various tools, to see if your data or keys are being exfiltrated. I freely acknowledge that this is a big project that requires specialized expertise — you will not finish it by yourself in a weekend (as commenters on HN have politely pointed out to me.) Still, reverse-engineering WhatsApp’s client code is entirely possible and various parts of the app have indeed been reversed several times by various security researchers. The answer really is knowable, and if there is a crime, then the evidence is almost certainly* right there in the code that we’re all running on our phones.

If you’re going to (metaphorically) commit a crime, doing it in a forensically-detectable manner is very stupid.

But WhatsApp is known to leak metadata / backup data / business communications…!

Several online commenters have pointed out that there are loopholes in WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption guarantees. These include certain types of data that are explicitly shared with WhatsApp, such as business communications (when you WhatsApp chat with a company, for example.) In fairness, both WhatsApp and the lawsuit are very clear about these exceptions.

These exceptions are real and important. WhatsApp’s encryption protects the content of your messages, it does not necessarily protect information about who you’re talking to, when messages were sent, and how your social graph is structured. WhatsApp’s own privacy materials talk about how personal message content is protected while other categories of data exist.

Another big question for any E2E encrypted messaging app is what happens after the encrypted message arrives at your phone and is decrypted. For example, if you choose to back up your phone to a cloud service, this often involves sending plaintext copies of your message to a server that is not under your control. Users really like this, since it means they can re-download their chat history if they lose a phone. But it also presents a security vulnerability, since those cloud backups are not always encrypted.

Unfortunately, WhatsApp’s backup situation is complex. Truthfully, it’s more of a Choose Your Own Adventure novel:

- If you use native device backup on iOS or Android devices (for example, iCloud device backup or the standard Android/Google backup), your WhatsApp message database may be included in a device backup sent to Apple or Google. Whether that backup is end-to-end encrypted depends on what your provider supports and what you’ve enabled. On Apple platforms, for example, iCloud backups can be end-to-end encrypted if you enable Apple’s Advanced Data Protection feature, but won’t be otherwise. Note that in both cases, the backup data ends up with Apple or Google and not with Meta as the lawsuit alleges. But this still sucks.

- WhatsApp has its own backup feature (actually, it has more than one way to do it.) WhatsApp supports end-to-end encrypted backups that can be protected with a password, a 64-digit key, and (more recently) passkeys. WhatsApp’s public docs are here and WhatsApp’s engineering writeup of the key-vault design is here. Conceptually, this is an interesting compromise: it reduces what cloud providers can read, but it introduces new key-management and recovery assumptions (and, depending on configuration, new places to attack). Importantly, even if you think backups are a mess — and they often are — this is still a far cry from the effortless, universal access alleged in this lawsuit.

Finally, WhatsApp has recently been adding AI features. If you opt into certain AI tools (like message summaries or writing help), some content may be send off-device for processing a system WhatsApp calls “Private Processing,” which is built around Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs). WhatsApp’s user-facing overview is here, Meta’s technical whitepaper is here, and Meta’s engineering post is here. This capability should not reveal plaintext data to Meta, either: more importantly, it’s brand new and much more recent than the allegations int he lawsuit.

As a technologist, I love to write about the weaknesses and limitations of end-to-end encryption in practice. But it’s important to be clear: none of these loopholes stuff can account for what’s being alleged in this lawsuit. This lawsuit is claiming something much more deliberate and ugly.

Trusting trust

When I’m speaking to laypeople, I like to keep things simple. I tell them that cryptography allows us to trust our machines. But this isn’t really an accurate statement of what cryptography does for us. At the end of the day, all cryptography can really do is extend trust. Encryption protocols like Signal allow us to take some anchor-point we trust — a machine, a moment in time, a network, a piece of software — and then spread that trust across time and space. Done well, cryptography allows us to treat hostile networks as safe places; to be confident that our data is secure when we lose our phones; or even to communicate privately in the presence of the most data-hungry corporation on the planet.

But for this vision of cryptography to make sense, there has to be trust in the first place.

It’s been more than forty years since Ken Thompson delivered his famous talk, “Reflections on Trusting Trust“, which pointed out how there is no avoiding some level of trust. Hence the question here is not: should we trust someone. That decision is already taken. It’s: should we trust that WhatsApp is not running the biggest fraud in technology history. The decision to trust WhatsApp on this point seems perfectly reasonable to me, in the absence of any concrete evidence to the contrary. In return for making that assumption, you get to communicate with the three billion people who use WhatsApp.

But this is not the only choice you can make! If you don’t trust WhatsApp (and there are reasonable non-conspiratorial arguments not to), then the correct answer is to move to another application; I recommend Signal.

Notes:

* Without leaving evidence in the code, WhatsApp could try to compromise the crypto purely on the server side, e.g., by running man-in-the-middle attacks against users’ key exchanges. This has even been proposed by various government agencies, as a way to attack targeted messaging app users. The main problem with this approach is the need to “target”. Performing mass-scale MITM against WhatsApp users in a manner described by this complaint would require (1) disabling the security code system within the app, and (2) hoping that nobody ever notices that WhatsApp servers are distributing the wrong keys. This seems very unlikely to me.