Recently I came across a fantastic new paper by a group of NYU and Cornell researchers entitled “How to think about end-to-end encryption and AI.” I’m extremely grateful to see this paper, because while I don’t agree with every one of its conclusions, it’s a good first stab at an incredibly important set of questions.

I was particularly happy to see people thinking about this topic, since it’s been on my mind in a half-formed state this past few months. On the one hand, my interest in the topic was piqued by the deployment of new AI assistant systems like Google’s scam call protection and Apple Intelligence, both of which aim to put AI basically everywhere on your phone — even, critically, right in the middle of your private messages. On the other hand, I’ve been thinking about the negative privacy implications of AI due to the recent European debate over “mandatory content scanning” laws that would require machine learning systems to scan virtually every private message you send.

While these two subjects arrive from very different directions, I’ve come to believe that they’re going to end up in the same place. And as someone who has been worrying about encryption — and debating the “crypto wars” for over a decade — this has forced me to ask some uncomfortable questions about what the future of end-to-end encrypted privacy will look like. Maybe, even, whether it actually has a future.

But let’s start from an easier place.

What is end-to-end encryption, and what does AI have to do with it?

From a privacy perspective, the most important story of the past decade or so has been the rise of end-to-end encrypted communications platforms. Prior to 2011, most cloud-connected devices simply uploaded their data in plaintext. For many people this meant their private data was exposed to hackers, civil subpoenas, government warrants, or business exploitation by the platforms themselves. Unless you were an advanced user who used tools like PGP and OTR, most end-users had to suffer the consequences.

And (spoiler alert) oh boy, did those consequences turn out to be terrible.

Around 2011 our approach to data storage began to evolve. This began with messaging apps like Signal, Apple iMessage and WhatsApp, all of which began to roll out default end-to-end encryption for private messaging. This technology changed the way that keys are managed, to ensure that servers would never see the plaintext content of your messages. Shortly afterwards, phone (OS) designers like Google, Samsung and Apple began encrypting the data stored locally on your phone, a move that occasioned some famous arguments with law enforcement. More recently, Google introduced default end-to-end encryption for phone backups, and (somewhat belatedly) Apple has begun to follow.

Now I don’t want to minimize the engineering effort required here, which was massive. But these projects were also relatively simple. By this I mean: all of the data encrypted in these projects shared a common feature, which is that none of it needed to be processed by a server.

The obvious limitation of end-to-end encryption is that while it can hide content from servers, it can also make it very difficult for servers to compute on that data.1 This is basically fine for data like cloud backups and private messages, since that content is mostly interesting to clients. For data that actually requires serious processing, the options are much more limited. Wherever this is the case — for example, consider a phone that applies text recognition to the photos in your camera roll — designers typically get forced into a binary choice. On the one hand they can (1) send plaintext off to a server, in the process resurrecting many of the earlier vulnerabilities that end-to-end encryption sought to close. Or else (2) they can limit their processing to whatever can be performed on the device itself.

The problem with the second solution is that your typical phone only has a limited amount of processing power, not to mention RAM and battery capacity. Even the top-end iPhone will typically perform photo processing while it’s plugged in at night, just to avoid burning through your battery when you might need it. Moreover, there is a huge amount of variation in phone hardware. Some flagship phones will run you $1400 or more, and contain onboard GPUs and neural engines. But these phones aren’t typical, in the US and particularly around the world. Even in the US it’s still possible to buy a decent Android phone for a couple hundred bucks, and a lousy one for much less. There is going to be a vast world of difference between these devices in terms of what they can process.

So now we’re finally ready to talk about AI.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably noticed the explosion of powerful new AI models with amazing capabilities. These include Large Language Models (LLMs) which can generate and understand complex human text, as well as new image processing models that can do amazing things in that medium. You’ve probably also noticed Silicon Valley’s enthusiasm to find applications for this tech. And since phone and messaging companies are Silicon Valley, your phone and its apps are no exception. Even if these firms don’t quite know how AI will be useful to their customers, they’ve already decided that models are the future. In practice this has already manifested in the deployment of applications such as text message summarization, systems that listen to and detect scam phone calls, models that detect offensive images, as well as new systems that help you compose text.

And these are obviously just the beginning.

If you believe the AI futurists — and in this case, I actually think you should — all these toys are really just a palate cleanser for the main entrée still to come: the deployment of “AI agents,” aka, Your Plastic Pal Who’s Fun To Be With.

In theory these new agent systems will remove your need to ever bother messing with your phone again. They’ll read your email and text messages and they’ll answer for you. They’ll order your food and find the best deals on shopping, swipe your dating profile, negotiate with your lenders, and generally anticipate your every want or need. The only ingredient they’ll need to realize this blissful future is virtually unrestricted access to all your private data, plus a whole gob of computing power to process it.

Which finally brings us to the sticky part.

Since most phones currently don’t have the compute to run very powerful models, and since models keep getting better and in some cases more proprietary, it is likely that much of this processing (and the data you need processed) will have to be offloaded to remote servers.

And that’s the first reason that I would say that AI is going to be the biggest privacy story of the decade. Not only will we soon be doing more of our compute off-device, but we’ll be sending a lot more of our private data. This data will be examined and summarized by increasingly powerful systems, producing relatively compact but valuable summaries of our lives. In principle those systems will eventually know everything about us and about our friends. They’ll read our most intimate private conversations, maybe they’ll even intuit our deepest innermost thoughts. We are about to face many hard questions about these systems, including some difficult questions about whether they will actually be working for us at all.

But I’ve gone about two steps farther than I intended to. Let’s start with the easier questions.

What does AI mean for end-to-end encrypted messaging?

Modern end-to-end encrypted messaging systems provide a very specific set of technical guarantees. Concretely, an end-to-end encrypted system is designed to ensure that plaintext message content in transit is not available anywhere except for the end-devices of the participants and (here comes the Big Asterisk) anyone the participants or their devices choose to share it with.

The last part of that sentence is very important, and it’s obvious that non-technical users get pretty confused about it. End-to-end encrypted messaging systems are intended to deliver data securely. They don’t dictate what happens to it next. If you take screenshots of your messages, back them up in plaintext, copy/paste your data onto Twitter, or hand over your device in response to a civil lawsuit — well, that has really nothing to do with end-to-end encryption. Once the data has been delivered from one end to the other, end-to-end encryption washes its hands and goes home

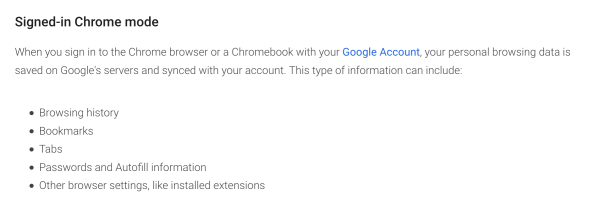

Of course there’s a difference between technical guarantees and the promises that individual service providers make to their customers. For example, Apple says this about its iMessage service:

I can see how these promises might get a little bit confusing! For example, imagine that Apple keeps its promise to deliver messages securely, but then your (Apple) phone goes ahead and uploads (the plaintext) message content to a different set of servers where Apple really can decrypt it. Apple is absolutely using end-to-end encryption in the dullest technical sense… yet is the statement above really accurate? Is Apple keeping its broader promise that it “can’t decrypt the data”?

Note: I am not picking on Apple here! This is just one paragraph from a security overview. In a separate legal document, Apple’s lawyers have written a zillion words to cover their asses. My point here is just to point out that a technical guarantee is different from a user promise.

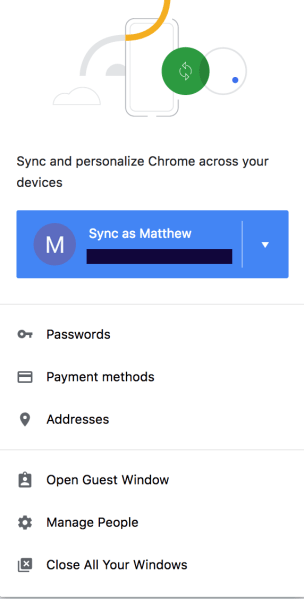

Making things more complicated, this might not be a question about your own actions. Consider the promise you receive every time you start a WhatsApp group chat (at right.) Now imagine that some other member of the group — not you, but one of your idiot friends — decides to turn on some service that uploads (your) received plaintext messages to WhatsApp. Would you still say the message you received still accurately describes how WhatsApp treats your data? If not, how should it change?

In general, what we’re asking here is a question about informed consent. Consent is complicated because it’s both a moral concept and also a legal one, and because the law is different in every corner of the world. The NYU/Cornell paper does an excellent job giving an overview of the legal bits, but — and sorry to be a bummer here — I really don’t want you to expect the law to protect you. I imagine that some companies will do a good job informing their users, as a way to earn trust. Other companies, won’t. Here in the US, they’ll bury your consent inside of an inscrutable “terms of service” document you never read. In the EU they’ll probably just invent a new type of cookie banner.

So to summarize: in the near term we’re headed to a world where we should expect increasing amounts of our data to be processed by AI, and a lot of that processing will (very likely) be off-device. Good end-to-end encrypted services will actively inform you that this is happening, so maybe you’ll have the chance to opt-in or opt-out. But if it’s truly ubiquitous (as our futurist friends tell us it will be) then probably your options will be end up being pretty limited.

Fortunately all is not lost. In the short term, a few people have been thinking hard about this problem.

Trusted Hardware and Apple’s “Private Cloud Compute”

The good news is that our coming AI future isn’t going to be a total privacy disaster. And in large part that’s because a few privacy-focused companies like Apple have anticipated the problems that ML inference will create (namely the need to outsource processing to better hardware) and have tried to do something about it. This something is essentially a new type of cloud-based computer that Apple believes is trustworthy enough to hold your private data.

Quick reminder: as we already discussed, Apple can’t rely on every device possessing enough power to perform inference locally. This means inference will be outsourced to a remote cloud machine. Now the connection from your phone to the server can be encrypted, but the remote machine will still receive confidential data that it must see in cleartext. This poses a huge risk at that machine. It could be compromised and the data stolen by hackers, or worse, Apple’s business development executives could find out about it.

Apple’s approach to this problem is called “Private Cloud Compute” and it involves the use of special trusted hardware devices that run in Apple’s data centers. A “trusted hardware device” is a kind of computer that is locked-down in both the physical and logical sense. Apple’s devices are house-made, and use custom silicon and software features. One of these is Apple’s Secure Boot, which ensures that only “allowed” operating system software is loaded. The OS then uses code-signing to verify that only permitted software images can run. Apple ensures that no long-term state is stored on these machines, and also load-balances your request to a different random server every time you connect. The machines “attest” to the application software they run, meaning that they announce a hash of the software image (which must itself be stored in a verifiable transparency log to prevent any new software from surreptitiously being added.) Apple even says it will publish its software images (though unfortunately not [update: all of] the source code) so that security researchers can check them over for bugs.

The goal of this system is to make it hard for both attackers and Apple employees to exfiltrate data from these devices. I won’t say I’m thrilled about this. It goes without saying that Apple’s approach is a vastly weaker guarantee than encryption — it still centralizes a huge amount of valuable data, and its security relies on Apple getting a bunch of complicated software and hardware security features right, rather than the mathematics of an encryption algorithm. Yet this approach is obviously much better than what’s being done at companies like OpenAI, where the data is processed by servers that employees (presumably) can log into and access.

Although PCC is currently unique to Apple, we can hope that other privacy-focused services will soon crib the idea — after all, imitation is the best form of flattery. In this world, if we absolutely must have AI everywhere, at least the result will be a bit more secure than it might otherwise be.

Who does your AI agent actually work for?

There are so many important questions that I haven’t discussed in this post, and I feel guilty because I’m not going to get to them. I have not, for example, discussed the very important problem of the data used to train (and fine-tune) future AI models, something that opens entire oceans of privacy questions. If you’re interested, these problems are discussed in the NYU/Cornell paper.

But rather than go into that, I want to turn this discussion towards a different question: namely, who are these models actually going to be working for?

As I mentioned above, over the past couple of years I’ve been watching the UK and EU debate new laws that would mandate automated “scanning” of private, encrypted messages. The EU’s proposal is focused on detecting both existing and novel child sexual abuse material (CSAM); it has at various points also included proposals to detect audio and textual conversations that represent “grooming behavior.” The UK’s proposal is a bit wilder and covers many different types of illegal content, including hate speech, terrorism content and fraud — one proposed amendment even covered “images of immigrants crossing the Channel in small boats.”

While scanning for known CSAM does not require AI/ML, detecting nearly every one of the other types of content would require powerful ML inference that can operate on your private data. (Consider, for example, what is involved in detecting novel CSAM content.) Plans to detect audio or textual “grooming behavior” and hate speech will require even more powerful capabilities: not just speech-to-text capabilities, but also some ability to truly understand the topic of human conversations without false positives. It is hard to believe that politicians even understand what they’re asking for. And yet some of them are asking for it, in a few cases very eagerly.

These proposals haven’t been implemented yet. But to some degree this is because ML systems that securely process private data are very challenging to build, and technical platforms have been resistant to building them. Now I invite you to imagine a world where we voluntarily go ahead and build general-purpose agents that are capable of all of these tasks and more. You might do everything in your technical power to keep them under the user’s control, but can you guarantee that they will remain that way?

Or put differently: would you even blame governments for demanding access to a resource like this? And how would you stop them? After all, think about how much time and money a law enforcement agency could save by asking your agent sophisticated questions about your behavior and data, questions like: “does this user have any potential CSAM,” or “have they written anything that could potentially be hate speech in their private notes,” or “do you think maybe they’re cheating on their taxes?” You might even convince yourself that these questions are “privacy preserving,” since no human police officer would ever rummage through your papers, and law enforcement would only learn the answer if you were (probably) doing something illegal.

This future worries me because it doesn’t really matter what technical choices we make around privacy. It does not matter if your model is running locally, or if it uses trusted cloud hardware — once a sufficiently-powerful general-purpose agent has been deployed on your phone, the only question that remains is who is given access to talk to it. Will it be only you? Or will we prioritize the government’s interest in monitoring its citizens over various fuddy-duddy notions of individual privacy.

And while I’d like to hope that we, as a society, will make the right political choice in this instance, frankly I’m just not that confident.

Notes:

- (A quick note: some will suggest that Apple should use fully-homomorphic encryption [FHE] for this calculation, so the private data can remain encrypted. This is theoretically possible, but unlikely to be practical. The best FHE schemes we have today really only work for evaluating very tiny ML models, of the sort that would be practical to run on a weak client device. While schemes will get better and hardware will too, I suspect this barrier will exist for a long time to come.)