Recently a reader wrote in and asked if I would look at Sam Altman’s Worldcoin, presumably to give thoughts on it from a privacy perspective. This was honestly the last thing I wanted to do, since life is short and this seemed like an obvious waste of it. Of course a project devoted to literally scanning your eyeballs was up to some bad things, duh.

However: the request got me curious. Against my better judgement, I decided to spend a few hours poking around Worldcoin’s documentation and code — in the hope of rooting out the obvious technical red flags that would lead to the true Bond-villain explanation of the whole thing. Because surely there had to be one. I mean: eyeball scanners. Right?

More seriously, this post is my attempt to look at Worldcoin’s system from a privacy-skeptical point of view in order to understand how risky this project actually is. The risks I’m concerned about are twofold: (1) unintentional risks to users that could arise due to carelessness on Worldcoin’s part, and (2) “intentional” risks that could result from future business decisions (whether they are currently planned or not.)

For those who don’t love long blog posts, let me save you a bunch of time: I did not find as many red flags as I expected to. Indeed, while I’m still (slightly) leaning towards the idea that Worldcoin is the public face of some kind of moon-laser-esque evil plan, my confidence in that conclusion is lower than it was going in. Read on for the rest.

What is Worldcoin and why should I care?

Worldcoin is a new cryptocurrency funded by Sam Altman and run by Alex Blania. According to the project’s marketing material, the goal of the project is to service the “global unbanked“, which it will do by somehow turning itself into a form of universal basic income. While this doesn’t seem like much of a business plan, it’s pretty standard fare for a cryptocurrency project. Relatively few of these projects have what sound like “real use cases,” and it’s pretty common for projects to engage in behavior that amounts to “giving things away for free in the hope that somehow this will make everyone use the thing.”

What sets Worldcoin apart from other projects is that the free money comes with a surprising condition: in order to join the Worldcoin system and collect free tokens, users must hand over their eyeballs.

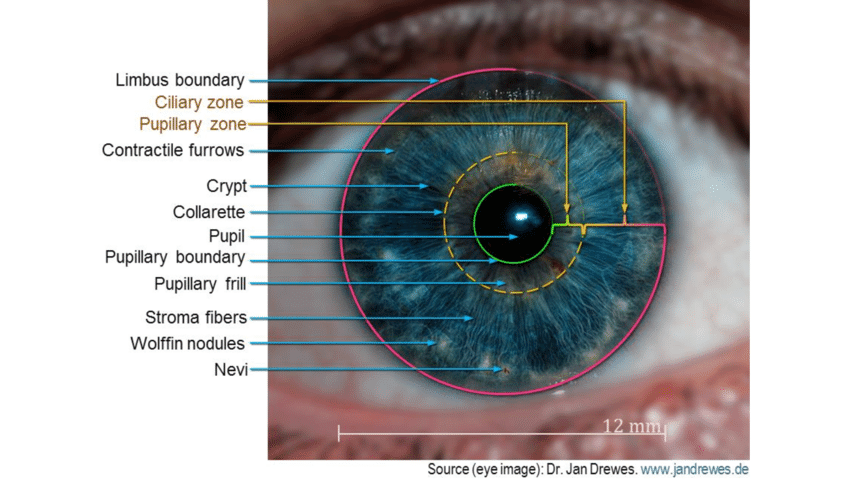

Ok, that’s obviously a bit dramatic. More seriously: the novel technical contribution of Worldcoin is a proprietary biometric sensor called “the orb”, which allows the system to uniquely identify users by scanning their iris, which not-coincidentally is one of the most entropy-rich biometric features that humans possess. Worldcoin uses these scans to produce a record that they refer to as a “proof of personhood”, a credential that will, according to the project, have many unspecified applications in the future.

Whatever the long term applications for this technology may be, the project’s immediate goal is to enroll hundreds of millions of eyeballs into their system, using the iris scan to make sure that no user can sign up twice. A number of people have expressed concern about the potential security and privacy risks of this plan. Even more critically, people are skeptical that Worldcoin might eventually misuse or exploit this vast biometric database it’s building.

Worldcoin has arguably made themselves more vulnerable to criticism by failing to articulate a realistic-sounding business case for its technology (as I said above, something that is common to many cryptocurrency projects.) The project has instead argued that their biometric database either won’t or can’t be abused — due to various privacy-preserving features they’ve embedded into it.

Worldcoin’s claims

Worldcoin makes a few important claims about their system. First, they insist that the iris scan has exactly one purpose: to identify duplicate users at signup. In other words, they only use it to keep the same user from enrolling multiple times (and thus collecting duplicate rewards.) They have claimed — though not particularly consistently, see further below! — that your iris itself will not serve as any kind of backup “secret key” for accessing wallet funds or financial services.

This is a pretty important claim! A system that uses iris codes only to recognize duplicate users will expose its users to relatively few direct threats. That is, the worst an attacker can do is find ways to defraud Worldcoin directly. By contrast, a system that uses biometrics to authorize financial transactions is potentially much more dangerous for users. TL;DR if iris scans can be used to steal money, the whole system is quite risky.

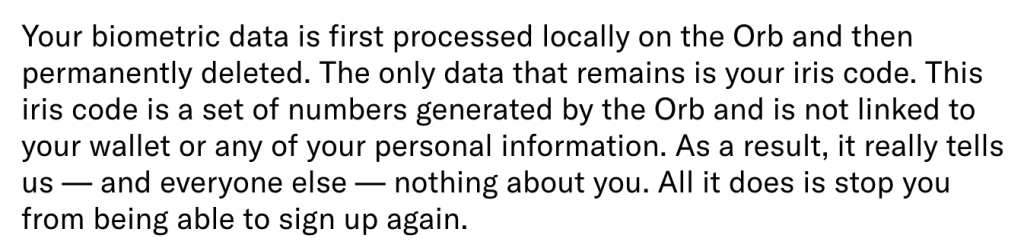

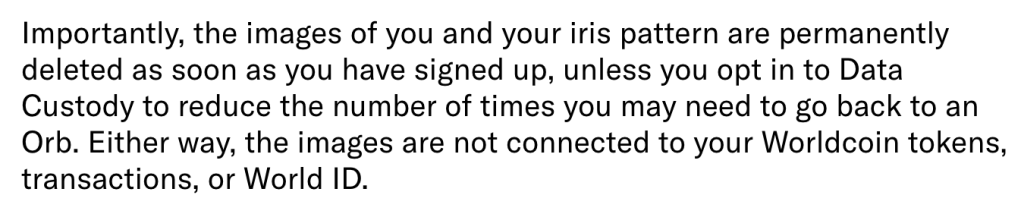

Second, Worldcoin claims that it will not store raw images of your actual iris — unless you ask them to. They will only store a derived value called an “iris code”:

The final claim that Worldcoin makes is that they will not tie your biometric to a substantial amount of personal or financial data, which could make their database useful for tracking. They do this by making the provision of personally identifiable information (PII) “optional” rather than mandatory. And further, they use technology to make it impossible for the company to tie blockchain transactions back to your iris record:

There are obviously still some concerns in here: notably the claim that you “do not need” any personal information does leave room for people to ‘voluntarily’ provide it. This could be a problem in settings where unsupervised Worldcoin contractors are collecting data in relatively poor communities. And frankly it’s a little weird that Worldcoin allows users to submit this data in the first place, if they don’t have plans to do things with it.

Worldcoin in a technical nutshell

NB: Much of the following is based on Worldcoin’s own documentation, as well as a review of some of their contract code. I have not verified all of this, and portions may be incorrect.

Worldcoin operates two different technologies. The first is a standard EVM-based cryptocurrency token (ERC20), which operates on the “Layer 2” Optimism blockchain. The company can create tokens according to a limited “inflation supply” model and then give them away to people. Mostly this part of the project is pretty boring, although there are some novel aspects to Worldcoin’s on-chain protocol that impact privacy. (I’ll discuss those further below.)

The novel element of Worldcoin is its biometric-based “proof of personhood” identity verification tech. Worldcoin’s project website handwaves a lot about future applications of the technology, many of them involving “AI.” For the moment this technology is used for one purpose: to ensure that each Worldcoin user has registered only once for its public currency airdrop. This assurance allows Worldcoin to provide free tokens to registered users, without worrying that the same person will receive multiple rewards.

To be registered into the system, users visit a Worldcoin orb scanning location, where they must verify their humanity to a real-life human operator. The orb purports to contain tamper-resistant hardware that can scan one or both of the user’s eyes, while also performing various tests to ensure that the eyeballs belong to a living, breathing human. This sensor takes high-resolution iris images, which are then then processed internally within the the orb using an algorithm selected by Worldcoin. The output of this process is a sort of “digest value” called an iris code.

Iris codes operate like a fuzzy “hash” of an iris: critically, one iris code can be compared to another code, such that if the “distance” between the pair is small enough, the two codes can be considered to derive from the same iris. That means the coding must be robust to small errors caused by the scanning process, and even to small age-related changes within the users’ eyes. (The exact algorithm Worldcoin uses for this today is not clear to me, since their documentation mentions two different approaches: one based on machine learning, and one using more standard image processing techniques.) In theory the use of iris code algorithms computed within tamper-resistant hardware should mean that your raw iris scans are safe — the orb never needs to output them, it can simply output this (hopefully) much less valuable iris code.

(In practice, however, this is not quite true: Worldcoin allows users to opt in to “data custody“, which means that their raw iris scans will also be stored by the project. Worldcoin claims that these images will be encrypted, though presumably using a key that the project itself holds. Custody is promoted as a way to enable updates to the iris coding algorithm without forcing users to re-scan their eyes at an orb. It is not clear how many users have opted in to this custody procedure, and it isn’t great.)

Once the orb has scanned a user, the iris code is uploaded to a server operated by the Altman/Blania company Tools for Humanity. The code may or may not be attached to other personal user information that Worldcoin collects, such as phone numbers and email addresses (Worldcoin’s documents are slightly vague on this point, except for noting that this data is “optional.”) The server now compares the new code against its library of previously-registered iris codes. If the new code is sufficiently “distant” from all previous codes, the system will consider this user to be a unique first-time registered user. (The documents are also slightly vague about what happens if they’re already registered, see much further below.)

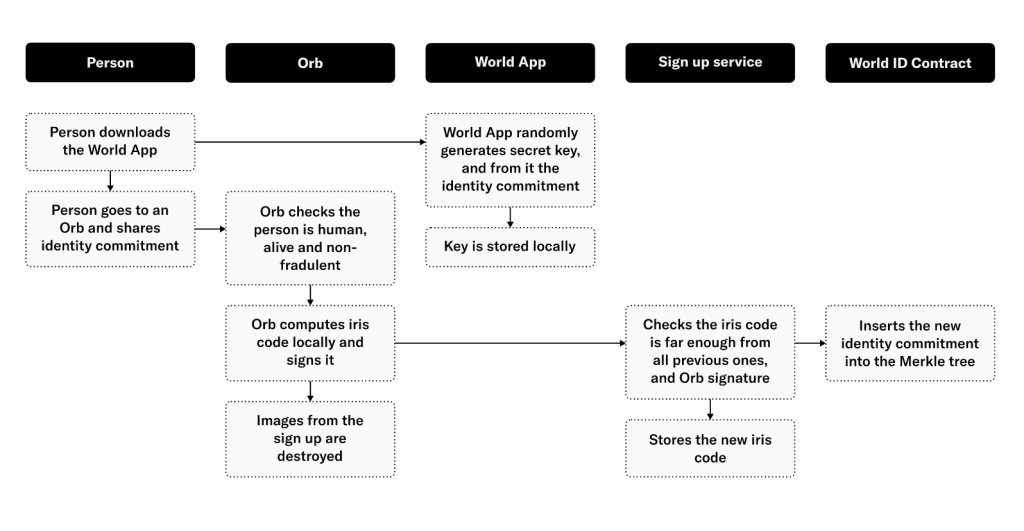

To complete the enrollment process, users download Worldcoin’s wallet software to generate two different forms of credential:

- A standard Ethereum wallet public and secret key, which is used to actually control funds in Worldcoin’s ERC20 contract.

- A specialized digital credential called an “identity commitment”, which comes with its own matching secret key material.

Critically, none of this key material is derived from the user’s biometric scan. The (public) “identity commitment”, is uploaded to Tools for Humanity, where it is stored in the database along with the user’s iris code, while all of the secret key material is stored locally on the user’s phone (with a possibility for cloud backup*). As a final step, Tools for Humanity exports the user’s identity commitment (but not the iris code data!) into a smart-contract-managed data structure that resides on Worldcoin’s blockchain.

Phew. Ok. Only one more thing.

As mentioned previously, the entire purpose of this iris scanning business is to allow users to perform assertions on their blockchain that “prove” they are unique human beings: the most obvious one being a request for airdropped tokens. (It is important to note that these assertions happen after the signup process, and only use the key material in your wallet: this means it’s possible to sell your identity data once you’ve been scanned into the system.)

From a privacy perspective, a very real concern with these assertions is that Worldcoin (aka Tools for Humanity) could monitor these on-chain transactions, and thus link the user’s wallet back to the unique biometric record it is associated with. This would instantly create a valuable source of linked biometric and financial data, which is one of the most obvious concerns about this type of system.

To their credit: Worldcoin seems to recognize that this is a problem. And their protocols address those concerns in two ways. First: they do not upload the user’s Ethereum wallet address to Tools for Humanity’s servers. This means that any financial transactions a user makes should not be trivially linkable to the user’s biometric credentials. (This obviously doesn’t make linkage impossible: transactions could be linked back to a user via public blockchain analysis at some later point.) But Worldcoin does try to avoid the obvious pitfall here.

This solves half the problem. However, to enable airdrops to a user’s wallet, Worldcoin must at some point link the user’s identity commitment to their wallet address. Implemented naively, this would seem to require a public blockchain transaction that would mention both a destination wallet address and an identity commitment — which would implicitly link these (via the binding known to the Tools for Humanity server) to the user’s biometric iris code. This would be quite bad!

Worldcoin avoids this issue in a clever way: their blockchain uses zero knowledge proofs to authorize the airdrop. Concretely, once an identity commitment has been placed on chain, the user can use their wallet to produce a privacy-preserving transaction that “proves” the following statement: “I know the secret key corresponding to a valid identity commitment on the chain, and I have not previously made a proof based on this commitment.” Most critically, this proof does not reveal which commitment the user is referencing. These protections make it relatively more difficult for any outside party (including Tools for Humanity) to link this transaction back to a user’s identity and iris code.

Worldcoin conducts these transactions using a zero-knowledge credential system called Semaphore (developed by the Ethereum project, using an architecture quite similar to Zcash.) Although there are a fabulous number of different ways this could all go wrong in practice (more on this below), from an architectural perspective Worldcoin’s approach seems well thought-out. Critically, it should serve to prevent on-chain airdrop transactions from being directly linked to the biometric identifiers that Tools for Humanity records.

To summarize all of the above… if Worldcoin works as advertised, the following should be true after you’ve registered and used the system:

- Tools for Humanity will have a copy of your iris code stored in its database.

- Tools for Humanity may also have stored a copy of your raw iris scans, assuming you “opted in” to data custody. (This data will be encrypted under a key TfH knows.)

- Tools for Humanity will store the mapping between each iris code and the corresponding “identity commitment”, which is essentially the public component of your ID credential.

- Tools for Humanity may have bound the iris code to other PII they optionally collected, such as phone numbers and email addresses.

- Tools for Humanity should not know your wallet address.

- All of your secret keys will be stored in your phone, and will not be backed up anywhere else unless you enable backups. (Worldcoin may also allow you to “recover” using your phone number, but this feature doesn’t work for me and so I’m not sure what it does.)

- If you conduct any transactions on the blockchain that reference the identity commitment, neither Worldcoin or TfH should be able to link these to your identity.

- Finally (and critically): no biometric information (or biometric-derived information) will be sent to the blockchain or stored on your phone.

As you can see, this system appears to avoid some of the more obvious pitfalls of a biometric-based blockchain system: crucially, it does not upload raw biometric information to a volunteer-run blockchain. Moreover, iris scans are not used to derive key material or to enable spending of cryptocurrency (though more on this below.) The amount of data linked to your biometric credential is relatively minimal (except for those phone numbers!), and transactions on chain are not easily linked back to the credential.

This architecture rules out many threats that might lead to your eyeballs being stolen or otherwise needing to be replaced.

What about future uses of iris data?

As I mentioned earlier, a system that only uses iris codes to recognize duplicate users poses relatively few threats to users themselves. By contrast, a system that uses biometrics to authorize financial transactions could potentially be much more risky. To abuse a cliché: if iris scans can be used to steal money, then users might need to sleep with their eyes open closed.

While it seems that Worldcoin’s current architecture does not authorize transactions using biometric data, this does not mean the platform will behave this way forever. The existence of a biometric database could potentially create incentives that force the company to put this data to more dangerous use.

Let me be more specific.

The most famous UX problem in cryptocurrency is that cryptocurrency’s “defining” feature — self-custody of funds — is incredibly difficult to use. Users constantly lose their wallet secret keys, and with them access to all of their funds. This problem is endemic even to sophisticated first-world cryptocurrency adopters who have access to bank safety-deposit boxes and dedicated hardware wallets. This is going to be an even more serious problem for a cryptocurrency that purports to be the global “universal basic income” for billions of people who lack those resources.

If Worldcoin is successful by its own standards — i.e., it becomes a billion-user global cryptocurrency — it’s going to have to deal with the fact that many users are going to lose their wallet secrets. Those folks will want to re-authorize themselves to get those funds back. Unlike most cryptocurrencies, Worldcoin’s biometric database provide the ultimate resource to make that possible.

At present the company cannot use biometrics to regain access to lose wallets, but they have many of the tools they need to get there. In the current system, the situation is as follows:

- In principle, Tools for Humanity’s servers can re-bind an existing iris code to a new identity commitment. They can then send that new commitment to the chain using a special call in the smart contract.

- While this could allow users to obtain a second airdrop (if Worldcoin/TfH choose to allow it), it would not (at present) allow a user to take control of an existing wallet.

To enable wallet recovery, therefore, Worldcoin would need to change its on-chain contracts This would involve either replacing the ERC20 contract with one that admits ID-authorized recovery, or — more practically — deploying a new form of smart contract wallet that allows users to “reset” ownership via an identity assertion. Worldcoin hasn’t done either of these things yet, and I’m curious to see how they will withstand the pressure in the long term.

What other privacy concerns are there?

Another obvious concern is that Tools for Humanity could use its biometric database as a kind of “stone soup” to build a future (and more privacy-invasive) biometric database, which could then be deployed for applications that have nothing to do with cryptocurrency. For example, an obvious application would be to record and authorize credit for customers who lack government-issued ID. This is the kind of thing I can see Silicon Valley VC investors getting very excited over.

There is nothing, in principle, stopping the project from pivoting in this direction in the future. On the other hand, a reasonable counterpoint is that if Worldcoin really wanted to do this, they could just have done it from the get-go: enrolling lots of people into some weird privacy-friendly cryptocurrency seems like a bit of a distraction. But perhaps I am not being imaginative enough.

A related concern is that Worldcoin might somehow layer further PII onto their existing database, or find other ways to make this data more valuable — even if the on-chain data is unlinkable. Some reports indicate that Worldcoin employees do collect phone numbers and other personally-identifying information as part of the enrollment process. It’s really not clear why Worldcoin would collect this data if it doesn’t plan to use it somehow in the future.

As a final matter, there is a very real possibility that Worldcoin somehow has the best intentions — and yet will just screw everythingup. Databases can be stolen. Zero-knowledge proofs are famously difficult to get right, and even small timing-based vulnerabilities can create a huge privacy leak: for example it should not be very hard to guess at the linkage between keys and identity commitments based solely on when the two are posted on chain.

Worldcoin’s system almost certainly deploys various back-end servers to assist with proof generation (e.g., to obtain Merkle paths) and the logs of these servers could further undermine privacy. This will only get worse as Worldcoin proceeds to “decentralize” the World ID database, whatever that entails.

Conclusion

I came into this post with a great deal of skepticism about Worldcoin: I was 100% convinced that the project was an excuse to bootstrap a valuable biometric database that would be used e-commerce applications, and that Worldcoin would have built their system to maximize the opportunities for data collection.

After poking around the project a bit, I’m honestly still a little bit skeptical. I think Worldcoin is — at some level — an excuse to bootstrap a valuable biometric database for e-commerce applications. But I would say my confidence level is down to about 40%. Mostly this is because I’m not able to come up with a compelling story for what an evil-future-Worldcoin will do with a big database that consists of iris codes plus a few phone numbers. And more critically, I’m pleasantly surprised by the amount of thought that Worldcoin has put into keep transaction data unlinked from its ID database.

No doubt there are still things that I’ve missed here, and perhaps others will chime in with some details and corrections. In the meantime, I still would not personally stick my eyeballs into the orb, but I can’t quite tell you how it would hurt.

Notes:

* When you sign up for WorldApp it gives you the option to back up your keys to your own provider, like iCloud. This is bad but not really Worldcoin’s fault. You can also provide your phone number for some sort of recovery purpose. What’s happening here is very interesting and I’d like to understand it better, but the feature simply did not work for me.

Great writeup of WorldCoin, thanks a lot. I was also very skeptical, but I am happy that you looked at it and got a better opinion.

Small typo: first paragraph in “Conclusion”: “would be used IN e-commerce”

As the corresponding secret key for the identity commitment is not created or stored within the phone’s secure enclave it can be stolen by malware harvesting such material and used to impersonate and authorize transactions. Users would need to periodically go back in person to an orb to refresh their identity commitment.

(And as far as the prospects for further PII data layered onto an identity in the database, users would need to submit this information and validate it is correct either by giving a selfie or coming in person with their government ID card. In which case an orb is unnecessary.)